9 Buildings That Prove Sustainable Architecture and High Design Are a Perfect Pair

Increasingly, climate change is a topic on people's minds. Over the past decade, the concern has manifested itself in everything from all-electric vehicles to solar-powered air travel . Eco-friendly living has even seeped into some of the largest man-made projects in the world: skyscrapers. Many might assume that green architecture can only be achieved at the expense of high design—but that is not the case. From the heart of midtown Manhattan and the Rick Cook–crafted Bank of America Tower to the verdant WOHA-designed Oasia Hotel in downtown Singapore, AD rounds up nine of the most sustainable skyscrapers on the planet that turn eco-friendly measures into beautiful design.

Bank of America Tower (New York City)

Designed by American architect Rick Cook, the Bank of America Tower in New York City is at the forefront of sustainable building with such features as floor-to-ceiling window glazing, which traps heat and maximizes natural light. What's more, the building collects rain water to reuse throughout the structure.

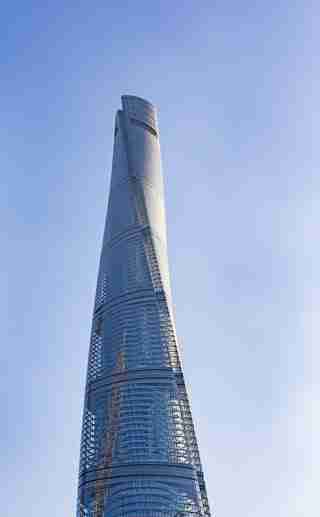

Shanghai Tower

The Gensler-designed Shanghai Tower is the second tallest building in the world (behind Dubai's Burj Khalifa). Towering 2,073 feet in the air, this skyscraper implements such advancements as a "transparent second skin," which consists of a double-glass façade that significantly reduces the building’s carbon footprint. A LEED Gold certified building, Shanghai Tower's exterior lighting is powered by wind-driven generators.

Bahrain World Trade Center

The Bahrain World Trade Center, designed by Atkins in 2008, has eco-friendly features including three skybridges holding wind turbines that generate power from strong breezes coming from the nearby Persian Gulf.

Pixel Building (Melbourne, Australia)

Melbourne's Pixel Building is a flashy example of green architecture. Designed by the Australian-based firm Studio505, the structure uses an intricate assembly of recycled colored panels to provide its occupants with maximized light control. It was thanks to such forward-thinking features that Pixel Building successfully became Australia's first carbon-neutral structure.

Taipei 101

The 1,667-foot-tall Taipei 101 skyscraper was designed in 2004 by C. Y. Lee. The building uses low-flow water fixtures that effectively reduce water usage by at least 30 percent compared to average building consumption and save roughly 7.4 million gallons of water each year.

One Central Park (Sydney, Australia)

Designed by the Pritzker Prize–winning architect Jean Nouvel, Sydney's One Central Park is as bold as it is eco-friendly. The structure is covered in 35 different species of plants, effectively trapping carbon dioxide, emitting oxygen, and providing energy-saving shade.

Oasia Hotel (Singapore)

The WOHA-designed Oasia Hotel in Singapore is a prime example of sustainable architecture meeting high design. Completed in 2016, the verdant building utilizes its many gaps and porous exterior to allow natural air to funnel in and around the interiors, thus saving on energy.

Apple Park (Cupertino, California)

For some, Apple Park will always be remembered as the final vision of the firm's inimitable founder, Steve Jobs. For countless more, however, Apple's latest headquarters will be considered the crowning architectural achievement for how the campus of a forward-thinking company should be designed. Created by the firm Foster + Partners, the 175-acre campus was the culmination of a dream that Jobs had in 2004 while walking through London's Hyde Park. It was while there that the iconic founder decided to house his company in a new environment where the barrier between building and nature seamlessly disappeared. To fulfill that lofty ambition, Jobs turned to Pritzker Prize–winning architect Norman Foster. "In my first meeting with Steve Jobs in 2009, he recalled the region [of central California] being the fruit bowl of America and the idea was born of re-creating such a landscape as an integral part of the concept," says Foster. "In this approach the buildings and their setting are inseparable and specific to the needs of Apple. Steve and I shared a vision for the project; Apple Park is the result of the coming together of two teams to ultimately become one." This vision includes a main, ring-shaped building that runs on fully sustainable energy, much of which comes from the solar panels that line the top of the spaceship-like structure. For a company as cutting-edge as Apple, solar-energy almost seems archaic. That's why it pushed Foster and his team further to create a building that actually breathes. Between each floor is a canopy that slightly sticks out, its main purpose being to protect employees from the intense California sun. Tucked within each canopy is a ventilation system that funnels air in and out of the building. Jobs (who was not a fan of air conditioning) wanted his employees to feel any passing breeze as if they were sitting outside. Through a variety of sensors, the building maintains a temperature of 68 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit, all by using an intake and release of natural air.

CopenHill (Copenhagen, Denmark)

Bjarke Ingels, the founding partner and creative director of Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), is no stranger to radical architecture. Yet, it's the design of CopenHill, a structure in his hometown of Copenhagen, that displays the sheer genius of the young architect. At its core, CopenHill is proof that eco-friendly architecture can be accomplished with high design. To that end, the eco-friendly waste-to-energy power plant emits no toxins into the atmosphere. Far from it. The structure can burn 400,000 tons of waste annually into enough clean energy to power 60,000 homes in the area. But it's not just about waste management—it's about having fun too. While Denmark receives a healthy amount of snow, the country is rather flat and not an ideal terrain for ski lovers. BIG took that fact and used it as an asset in its scheme. Atop the CopenHill roof is a nearly 1,500-foot-long ski slope, which is accessible through an elevator inside the building.