A Classically English Attitude

View Slideshow

Forty years of experience have taught me that decoration is a minor art," says London-based designer David Mlinaric, "very much dependent on the architect and the client. I am absolutely certain this is true." Though he is at the top of his profession—his work includes the Royal Opera House and rooms in both the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, as well as houses for J. Paul Getty, Jr. ( Architectural Digest , March 1998), and Lord Rothschild ( Architectural Digest , February 1991)—Mlinaric prefers to share the credit for even his most famous projects with the architects and clients.

The conversion of a residence in London called for just such a seamless collaboration. "There's no indication of where one person's ideas end and another's begin," says Mlinaric. "Anthony Collett, the architect, understands exactly how to create order and balance in a house, and the clients have an artistic sensibility. Every once in a while people come my way who have that extra dimension—Jacob Rothschild, Mick Jagger and the owners of this house. Their prompting made it almost impossible to go wrong."

The house was originally two houses, most likely built in the 1870s, though many visible signs of the buildings' history had been taken out over the years, so it is difficult to be precise. A previous owner had connected the two residences by randomly knocking out a few doors between them. "Our task," says Collett, "was to untangle everything, then crochet it back together as one house. Every wall came down; the staircase was the only thing we kept."

Collett adapts his style to suit the unique needs of each house he works on. "Proportions might be exaggerated for one project," he says, "restful for another. I see our role as master tailors, making certain the fit between client and building is right." He and his partner, Andrew Zarzycki, have designed some of the most beautiful new residences in London, just as they have bestowed a new rationale and dignity on old ones.

An early challenge on this project was the creation of a large entrance hall that would pull the two houses together and "help explain the length and the width of the house," says Collett. "We designed equal rooms—the breakfast room and the library—balanced on either side of the entrance hall, their doors lined up on axis to reinforce that balance. There's also a view straight through, all the way to the back. The entrance hall is the center, the pivot, for the entire house. It's an invisible, skeletal thing. What I did here was set up a structure for David's brilliance."

The brief was to create rooms that could be informal and comfortable but could also set the scene for the clients' frequent entertaining, whether it be lunch for a few friends, dinner for fifty or a reception for three hundred and fifty. "It was a big house with small rooms," Collett recalls. "They needed rooms that would have a presence. We opened up the entire space on the second floor to make one large U-shaped living room—front-to-back in each of the original houses, with a new connecting room between them. But for this level of entertaining, the house needed even more: It needed magic, something unexpected and dramatic. A dining room is the right place to do that, because it's a transient space; people are there to celebrate."

The architect suggested taking a floor out to make a double-height formal dining room. It was a good idea, but the owners quite understandably had doubts about the distance between the dining room and the living room. Would they have to shuttle guests to dinner in a tiny elevator? Not at all, Collett told them. "The journey from the living room down to the dining room is well paced, with rhythms of its own," he explains. "You walk down the main staircase, through the marble-floored entrance hall and along a balcony at the upper level of the dining room for a view down to the candlelit glamour of the table below. It's like coming into the upper rows of a theater, seeing a glowing and opulent set on the stage, then descending to be part of the performance. The staircase is deliberately narrow, a bit confining; guests lose sight of the room just before they emerge into it. The clients caught the excitement of it immediately. It was brave of them to trust us, and David continued in that spirit."

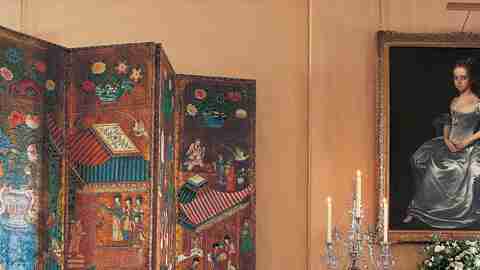

"A dinner party is a kind of theater," says Mlinaric. "I don't think any dining room or restaurant is complete without people in it. An empty library is all right, because it has books, but a dining room only comes to life when filled with people and food. We needed the right background for laughter and challenging conversation; we needed the contents to be high' decoratively, to animate such a large space. But the scheme needed time to develop."

Mlinaric believes that good houses take time and that the only way to create them is step by step. "These days people see something in a magazine and want the same thing in the next ten minutes," he says. "Serious decorating has much to learn from gardening. Plant a bit, prune a bit; put something in, withdraw something. We began by painting the walls pale terra-cotta and white—the colors of the Assembly Rooms in Bath. That gave the architecture a clarity, but it wasn't enough, and it was the clients themselves who encouraged more fantasy. The idea of painted panels that curtain the lower part of the room with the same striped taffeta hanging at the windows developed from there."

"Serious decorating has much to learn from gardening," says David Mlinaric.

Trees appear to grow on the walls; the painted grillwork balconies echo the house's real balconies. "It took an entire year to create the papier peint by hand," says Mlinaric, "but you don't get a house like this unless you give it time. The clients understood that. I'm only interested in doing a house if I know I can do it correctly." He illustrates his point by mentioning that he and his clients are still searching for a mirror for the living room. "There's a gap—and it will stay a gap—until we find the right thing to answer that suite of very fine French furniture," he says. "I couldn't work any other way.

Mlinaric's style is grounded in historical knowledge; he has a remarkable memory for architectural details, which conveniently surface in his mind when needed. "I can't remember anything else," he says. "Telephone numbers, the birthdays of my children—there's no hope. But I do seem to have clarity of recall for what I see and like. For the marble floor in the entrance hall, for example, I remembered a pattern in a floor that I saw years ago at Heveningham Hall in Suffolk. For the linking passage between the two living rooms, precedents in ancient Greece and Rome came to mind."

History's heroes are frequent companions for Mlinaric. Sir John Soane he admires "because he is so useful to designers in England, his work very borrowable, the details just right for English houses," he notes. "I also admire Sinan—the architect to Suleiman the Magnificent—and I admire practically everything in ancient Egypt. Nothing was ugly. Can you believe it, such a world where nothing was ugly? Color, shape—everything was beautiful."

The designer's curiosity about houses and the people who have lived in them is infinite, but his patience with anything he considers shoddy or vulgar is very short. He is generous in his praise of the skills of the craftspeople working in England and France today: "There are not as many as there were in the eighteenth century, but those that are good are as good as they were then." His criticism of those who fill their houses with inappropriate elements, however, is strong: "Nearly everybody adds something intrusive, something that goes against the bones of the place. Most living rooms are all lampshades, telephones and ashtrays."

Mlinaric and Collett worked closely on all of the house's architectural details. For the breakfast room, with its low ceiling, they designed paneling with a vertical emphasis and great refinement. A studio built by one of the residence's previous owners is reminiscent of those built into gardens for writers or artists in the nineteenth century, so they worked in the tradition of the Arts and Crafts Movement and used oak rather than mahogany. There Collett designed heavier cornices and rafters that do not copy any particular historical example but are appropriate in scale and spirit. "The intent was to work within the idiom—not to slavishly follow the rules but not to deface the building, either," he says. "There's a variety of detail, but the house was built in an eclectic era, so variety seems right."

David Mlinaric feels this house is one of the best he has ever done, and he is gratefully aware of the role the clients played throughout the course of the project. "No designer is any better than his clients," he says. "It's something I've been aware of for some time. Their input is what helped make this house that much better."