A Look at the Life of America’s Most Important Contemporary Woodworker

The designer George Nakashima was fond of saying that he kept some pieces of wood in his studio for long periods of time, and “it would only be after 10 years that it would occur to him what to do with them,” recalls his nephew, John Nakashima.

George’s bewitchingly elegant wooden furniture, which emphasizes the unique shape, spirit, and peculiarities of it material, is now a cornerstone of 20th-century design, but as John details in his new documentary, George Nakashima: Woodworker , his uncle came to his profession, and his artistic sensibility, only after similarly prolonged deliberation in his 30s. “He just didn’t happen into his career,” John says. He decided that “he was going to find a reason to create.”

An archival image of George Nakashima with his daughter, Mira.

The illuminating film, tenderly narrated by John, a producer for West Virginia Public Broadcasting, will have its premiere run from Friday evening through Sunday on Design Miami’s website . It follows the future icon from his birth to first-generation Japanese immigrants in Spokane, Washington, in 1905, through his architecture studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and on to his travel, beginning in 1931, via an around-the-world steamship ticket.

An iconic Nakashima table and chairs.

George encountered modernism in France and marveled at the communal efforts that forged its grand Gothic churches. “We have these trillions of dollars of gross national project, but we couldn’t begin to put up the cathedral of Chartres,” he said in an interview recorded late in his life. (He died in 1990, at age 85.) In Japan, Nakashima immersed himself in Shinto beliefs, met his future wife, Marion Okajima, and worked with onetime Frank Lloyd Wright employee Antonin Raymond.

Raymond’s Golconde Dormitory—the first reinforced concrete structure in India—for Sri Aurobindo’s ashram took Nakashima to Pondicherry in the 1930s. While there, he began constructing furniture, became a disciple of the guru, and saw that “life, the act of creating, and spirituality can all be one,” John says in the film.

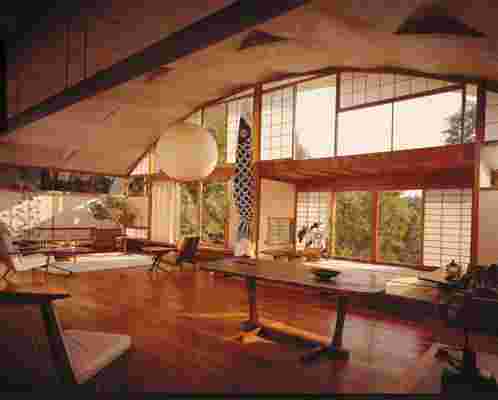

Inside the Conoid Studio at the Nakashima compound in New Hope, Pennsylvania.

Shortly after returning to the United States, the shameful internment of Japanese Americans occasioned another breakthrough for Nakashima; imprisoned in an Idaho camp in 1942 with his wife and their infant daughter, Mira, he studied with an expert carpenter, Gentaro Hikogawa. “He concentrates on it in such an intense way it almost hurts,” George said of the master’s drive. In 1943, Raymond, now living in New Hope, Pennsylvania, secured the release of George, Marion, and Mira, though many of their close relatives remained detained. George bought land in the town, which is about an hour outside of Philadelphia, and started building a home and studio.

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

Today that estate houses George Nakashima Woodworkers , headed by Mira Nakashima, who worked closely with him and oversees the production of his designs. “The whole making of the film was a process of discovery for both of us,” says Mira, since she was researching a book on her father , “who didn’t talk much,” at the same time John was starting out.

For dealer and Nakashima expert Robert Aibel, who runs Moderne Gallery in Philadelphia, the film presents a chance to experience the designer’s life journey in full—and a chance to grasp his approach, which Nakashima detailed in his 1981 book, The Soul of a Tree . Despite fame and market demand, “there is a very limited understanding of the aesthetics and philosophy of his work,” Aibel says. “The seeming simplicity of what he made belies its aesthetic complexity.”

Original Nakashima sketches detailing his design process.

“When dad started out, he said it was kind of a derogatory term to call yourself a woodworker,” Mira says. “But that is what he said he wanted to be.” Now many young designers aspire to that title. The film, she believes, “will probably inspire a lot of woodworkers.”