A Shining Lone Star

View Slideshow

Looking today at the land that surrounds the Dallas home of Frederick Baron and Lisa Blue, one would be hard-pressed to describe it as either a "mess" or a "bramble." And under no circumstances now would you ever have to "hack your way in" to the flawless grounds.

But those are the words Robert A. M. Stern uses to describe the state of the property as he first laid eyes on it. With Baron and Blue, partners at the Dallas law firm Baron & Budd, the celebrated architect was touring the neighborhood in the company of a real estate agent—more or less incognito; she didn't quite know with whom she was dealing—searching for the right place to build. Stern had decisively rejected a long list of seemingly fit sites only to light up when the group, then near the end of the day and their patience, was shown the nine overgrown acres of the old Pollock estate.

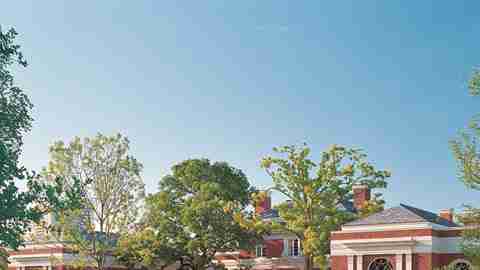

One might be forgiven for assuming at first that the house serves an institutional function—as the library of a small college, perhaps.

As Baron remembers it, they were standing among the creepers and weeds, noting the derelict vegetation, the scarcity of salvageable trees and the ample evidence that the neighborhood kids had made the place their own—more than ready to retreat, in other words—when Stern started to make his case. "Bob told us, You have just got to buy this property.'"

Its merits were not immediately clear. But Stern's eye carried the day, and the couple, for whom he had already built an impressive Lutyensesque house in Aspen, Colorado, bought the land. "Here was a flat site, almost square in proportion, that required definition," Stern says. Such a blank slate would serve perfectly to support what the architect calls an "unabashedly grand house," the program for which was already starting to take shape in discussions with his clients. The bramble, once it was cleared, would give him the opportunity to "place the house so that it would take command of the site in the way that classical buildings can do."

The result is a study in what Stern describes, with characteristic wit, as "English Regency sifted through American Federal." Of its size, he proudly notes the obvious: "It's big, and it looks big." Baron continues that theme: "We feel like we're in our own territory, our own little country."

Though the census of this nine-acre nation shows a population of only two, the borders are open, and the visitors are flooding in. In the tradition of the Pollock family, whose home—noted for its large swimming pool, one of the first in Dallas—had long been an important social center for the local Jewish community, Baron and Blue loan the house nearly every week for charitable events. The house is also an important fixture in Democratic Party politics, both local and national; Fred Baron is finance director for the presidential campaign of Senator John Edwards.

Robert A. M. Stern wanted to "place the house so that it would take command of the site in the way that classical buildings can do."

Because of its size and bearing, its brick-and-cast-stone rigor, its nearly public use, one might be forgiven for assuming at first that the house serves an institutional function—as the library of a small college, perhaps, or the Dallas outpost of the Frick. Not at all, say all concerned. Here it seems the architect did the impossible; with Armand LeGardeur, who led the project, and Ral Morillas, who was responsible for the interior design, Stern made this house—all 30 rooms and 21,000 square feet of it—feel like something less and something more than its scale suggests.

"It's an absolutely wonderful house," Baron says. "But I'll tell you something: It's also a wonderful home."

Concealing about two-thirds of the house, Stern oriented the main mass so that it is approached end-on. A short drive leads to a paved court flanked by the garage and natatorium in arch-cut volumes, long and low. Two of the site's older trees, a cedar elm and a pecan, stand on either side of the front door and its straightforward portico; the court was designed to spare them. "We didn't want people to be hit over the head with the size of the structure as they arrive," Stern says. "They discover the size of the house as it unfolds, which is just how it should be."

That process of unfolding begins just beyond the front door in the entrance hall, along an axis that leads all the way from the paved court to a lake defining the south edge of the property. The black-and-white-themed entrance hall centers on a compass rose device in the marble paving and serves as the terminus of the house's elliptical main stair.

People "discover the size of the house as it unfolds, which is just how it should be," says the architect.

From this space begins the sequence of public rooms, a T-shaped exercise in gracious enfilade: first the living room, opening through wide glass doors onto the second of the house's three semi-enclosed courts, then the conservatory ("the Sunday Times reading room," per Stern) with its kentia palms, limestone floors and lavish, deep latticework, white on green.

At the junction of the T, the conservatory gives way on one side to the paneled dining room, where 20 can sit at the three-pedestal table, and on the other to the library. There double rows of sconces and two 17th-century chandeliers play against the English brown-oak panels and pilasters, the capitals of which are each carved with a different Texas wildflower. Beyond these rooms, at the far ends of each wing, there is a breezeway porch, open on three sides through high arches but set back deep behind brick against the heat.

The formality of these spaces is undercut by design in several others. A small vestibule opening off the back of the conservatory is decorated floor to ceiling in applied seashells (Stern had been in Italy, where he "got into the grotto mode"). The spa, which provides a transition between the indoor lap pool and a leather-walled billiard room, is rendered as a series of nested, striped cabanas. And, thrusting out from the kitchen into a courtyard planted with crape myrtles, a cylindrical tempietto houses the breakfast room.

On the third floor, under the slopes of the slate roof, Stern has provided what Baron calls "the most magnificent workout area you can imagine." Underneath the gym equipment are Oriental rugs; two Warhol prints of Chairman Mao hang on the wall. On the second floor there is a sprawling five-room master suite, his-and-her studies opening onto a circular private terrace, and—perhaps surprisingly for such a large residence—a mere two guest rooms, in one of which the metaphorical light is always on for Stern.

"When you go through a house project with Bob, you become very close to him," Frederick Baron says. "He has a deal: When he's done a house, he has the right to stay there."

In that case, we can add another superlative to this exceptional house: It is certainly one of Robert A. M. Stern's finest pieds-à-terre. Indeed, with its clever planning, top-drawer materials, venerable proportions and courageous victory over difficult scale, the house seems likely to stand the very test of time it already appears so convincingly to have stood.