Aesthete Perfumier Frédéric Malle Reflects on 20 Years of Taste-Making

For Frédéric Malle, the man behind his namesake line of haute-couture-inspired perfumes, the idea of slowing down—a key topic of conversation recently among friends—has always been embedded in the DNA of the way he presents himself to the world. His brand, Éditions de Parfums Frédéric Malle, is celebrating its 20th anniversary this month, and commemorating the milestone has forced him to take a momentary pause.

“Looking back, and I don’t often like to, I think I’ve become way more serene about things,” he says over the phone from his home on Long Island. “I am still as obsessed and consumed with details as I once was, but I really have this notion that if something doesn’t work out, something else will. Things aren’t as dramatic as I think they once were.”

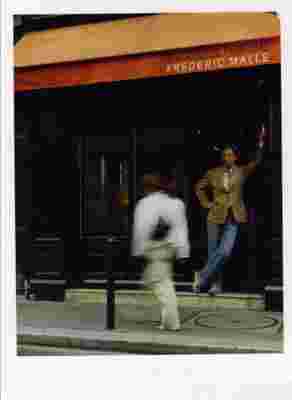

Frédéric Malle standing by the door at 37 rue de Grenelle, Paris, when it opened in 2000.

To celebrate his professional anniversary, there’s a book, Éditions de Parfums Frédéric Malle: The First Twenty Years ( Rizzoli, $75 ); a rerelease of seven of his most popular perfumes with an updated packaging iconography; and a new retail concept opening in China. And much like the nature of his stores, he’s taking the time to appreciate, well, time. “I knew the book by heart and I had been totally involved. It really shows, in one object, how much we had done in 20 years. And you have it compressed in your hands,” he says of the tome. “I must say, it was quite an emotional experience.”

Malle's 94 Greenwich Avenue, New York City, store. Total design by Steven Holl.

His boutiques, while widespread around the globe, cohesively exist to serve the same purpose: to unwind. “The purpose is always the same—to come inside and slow down,” he says. “The sense of time is hugely important. When people enter, I want them to slow down and to go from their everyday lives to a mood that is a little bit more reflective and have them think about where they would be when they wear the fragrances. In order to understand the circumstance in which they could be in, you need to make them feel comfortable, like they’re in a home.”

The “Smelling Column” in the 21 rue du Mont Thabor, Paris, store.

His approach to where he lives is very much similar to the way he tells his brand story through his brick-and-mortar locations—with one very small, yet very important, tactic. “I usually create a form of decor that feels like it has always been there, almost like a woman who gets out of the hairdresser and undoes her hair a little bit so she doesn’t look like a granny,” he says with a chuckle. “In my 18th-century apartment in Paris I used to have contemporary art and classic furniture. It’s the mix that I like to play with, but the stores are different in that when you go to an apartment, naturally, you’re in an intimate world. When you go to a store, the store has to do a little bit more to calm you down.”

The 898 Madison Avenue, New York City, store. Designed by Patrick Naggar.

It’s taken 20 years to master his tactics, but he’s pinpointed it to a science: Lighting is never too bright; wood panels adorn the walls to soothe; there’s always a table (often from his own collection), a sitting area, images of the perfumers above their creations, and, most important, his signature smelling booths. (“This is to perfume what mirrors are to garments.”) Together, it creates what he describes as “an attitude in a gallery-like setting.” And much like the red Bakelite cap that adorns the limited-edition 20th-anniversary perfumes, it’s a subtle reminder that his brand takes as much inspiration from the worlds of literature and art as it does from history.

The 37 rue de Grenelle, Paris, store. A space imagined by Frédéric Malle and Andrée Putman, and realized by Olivier Lempereur.

“I was inspired by the color combination of red, off-white, and black from Éditions Gallimard, a French publishing house that published most of the great French authors of the 20th century and still does today, and they always used that color code—just like Chanel has black-and-white,” he notes. “It’s this color combination that I associate with art and literature, and my idea was to refine the red, similar to that of both Prouvé and Calder, to remind people that they were dealing with perfumers and artists whose work is, well—it’s art.”