Contemporary Classicism

View Slideshow

Though it's hard to believe from its Neoclassical exterior and graciously settled feeling within, the summer retreat belonging to a New York-based couple came together in a mere three years. That time frame included drawing up plans, building the three-story structure, choosing the furnishings, deciding on wallcoverings and fixtures and attending to all the myriad details that, through labor and love, transform a house into a home. "We selected the fabrics and then worked from the inside out," says John Ike, of the firm Ike Kligerman Barkley, who acted as both architect and design consultant alongside project designer Terry Ricci. "We did the colors inside and then talked about what to do outside."

The couple, a businessman and his wife, with five children ranging in age from twelve to twenty-five, were well acquainted with the area, a small and quiet seaside community in New Jersey about an hour's drive from Manhattan. The husband spent summers not far from there, and the family had owned the property for about ten years before deciding to build. They chose Ike for his work on other houses and, perhaps more important, for his temperament. "He doesn't get crazed," says the wife. "He has a very calm way about him, and he deals nicely with people." She also credits the quick turnaround to her own personality. "Once I make a decision, that's it. I don't stall and hem and haw."

"The Tuscan Columns And Double-Story Order Lend A Grand Scale To The Composition."

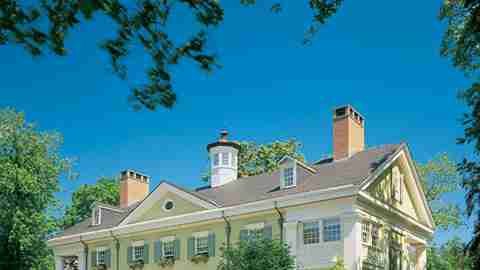

The most basic decision, of course, was what kind of house to construct. At first the couple leaned toward a Shingle Style exterior with Arts and Crafts furnishings. Ike steered them in the direction of Charles A. Platt, a turn-of the-last-century architect and landscape designer who created summer houses for old New York families. "He did a number of them that were classical and symmetrical, but not so uptight as to be unlivable," notes Ike. The first-floor rooms all have doors leading to spacious porches or to the broad, simply landscaped grounds in the rear. One façade, called a temple front, was a popular fixture in Platt houses. "The Tuscan columns and double-story order lend a grand scale to the composition," says Ike.

Inside, the details have been kept lowkey to give pride of place to the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American and English antiques purchased specifically for the house. "We bid on a lot of furniture before it was even standing, as we were working on the plans," explains the wife. "Things came up at auction, and we said, Oh, we'll find a place for them.'"

The resulting arrangements are harmonious because of careful attention to colors and fabrics. Ike persuaded the clients to hire color specialists Donald Kaufman and his wife, Taffy Dahl, for ideas. They were skeptical at first—"Why on earth do we need someone to consult on colors?" the husband asked—but were pleased with the results. The subtle palette throughout helps knit together the twelve rooms and 7,500 square feet of living space.

The first area to greet family and visitors is an amply lit entrance hall whose focal point is a cascading stairway modeled after designs by Henry Hobson Richardson, the Beaux-Arts-educated architect responsible for the Romanesque Revival in the United States. Maple latticework on the walls, inspired by the work of McKim, Mead White, is a major decorative element and acts as a kind of bridge between the geometries of the quilt and the hooked rug.

In the living, dining and family rooms, a few contemporary pieces have been thrown into the mix. Yet even some of the more ornate treasures, among them Oriental lamps and bibelots, tie in with the Americana because of the busy nineteenth-century import-export trade. For the dining room, Ike and his clients chose Zuber scenic wallpaper—also used in one of the rooms at the White House and still manufactured from the original 1834 plates. Different views show Boston Harbor, Niagara Falls and a peaceable meeting with Native Americans.

Upstairs, the rooms have been arranged to accommodate the members of the family. The four boys are paired off in two suites of separate bedrooms with shared baths, grouped at one end of the broad hall. The daughter has her own quarters. One of the more ingenious features of the bedrooms is built-in cupboards instead of closets. In the master bedroom, a screen wall serves as a backdrop for the bed and creates a vestibule that gives way to the generous dressing room, which, the wife points out, is "almost decadent."

In summer many of the family's activities center around the pool, invisible from the house behind a tall hedge. The poolhouse is, according to John Ike, a kind of "folly with classical associations," or, in simpler terms, "a baby version of a Platt design." Together with landscape architect Steven R. Krog, the clients worked to preserve several large old trees in the backyard.

With its pleasant yellow-and-green façade and deeply shaded rear lawn, the house seems to be a visual metaphor for what Henry James called the two most beautiful words in the English language: "summer afternoon." In colder months, says the wife, "I miss it every day."