Inside Frank Lloyd Wright’s Major MoMA Exhibition

One of the bolder, brasher visionaries in our country’s cultural history, Frank Lloyd Wright might be the only architect with a household name—and not just because Simon and Garfunkel sang about him or Lego has miniaturized six of his designs. A daring innovator with an eye for geometric harmony, Wright epitomized the modern ingenuity that shaped American identity in the first half of the 20th century. And while he created about 1,000 projects, nearly half of which were realized (some after his death in 1959), most people known him only for such tourist-magnet masterpieces as Fallingwater , the impossibly cantilevered residence atop a waterfall in southwestern Pennsylvania, or the Guggenheim Museum in New York, his ingenious experiment in spiraling concrete.

But his legacy is soon to be expanded just as we hit his 150th birthday this week , fittingly. “ Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive ,” opening at the Museum of Modern Art on June 12, brings together some lesser-known but no less fascinating or influential projects from the gargantuan Frank Lloyd Wright Archive, which MoMA and Columbia University jointly acquired in 2012. Tasked with tackling the nearly 500,000 items, MoMA curator and Columbia professor Barry Bergdoll unleashed 14 scholars into its stacks to unearth some of its many curiosities. “I thought a show of masterpieces from the Frank Lloyd Wright Archive would be boring,” says Bergdoll. “And I wanted to show what a difference it will make to have the archive at a museum and university.” (The archive was previously housed at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation outside Scottsdale, Arizona.)

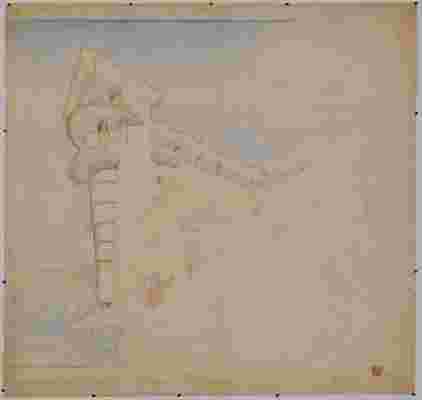

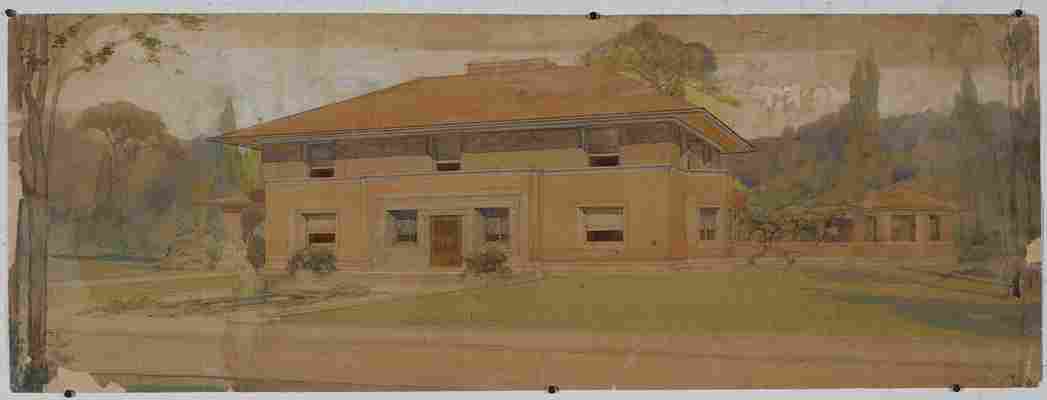

Wright’s projects here range from the pragmatic to the utterly fantastic, including a mile-high skyscraper designed for Chicago in 1956. “When you’re among the great architects of the 20th century, you want to dream of an architecture that might not yet be possible,” says Bergdoll. An urban development plan from 1926 shows Wright already rethinking the relationship of the car to the city, with underground parking and raised sidewalks, while his 1915–1917 kit-built homes reveal his drive to merge mass production and craftsmanship. Restored Utopian schools for African American children in the rural South and Depression-era experimental small farms color some of his stunning residences in a more socially progressive light. “I don’t think people are going to go away thinking that they have a nice, full but different view of Frank Lloyd Wright,” says Bergdoll. “But they will find someone who was continually experimenting and taking on new challenges and remains a very engaged, vital, controversial force.”

Here, AD gets an exclusive first look at highlights from the upcoming exhibition.