Jean Nouvel Explains His Latest Design—A Resort Hidden Within the Rocks of Saudi Arabia

“I have a lot of admiration for the desert,” says Jean Nouvel. “The desert, for me, is a totally metaphysical dimension, surely a poetic dimension. We vanish in the middle of it, are alone in the middle of its vastness.” The storied layers of this particularly demanding topography have inspired the Pritzker Prize–winning architect throughout his career, from the Louvre Abu Dhabi to the National Museum of Qatar that takes its shape from a symbolic “desert rose.” And now it will also be the case with his newest design: Sharaan Nature Reserve, a resort hidden within the rock dwellings of AlUla, in northwest Saudi Arabia.

This new undertaking means that Nouvel begins a sensory journey inviting visitors for the very first time to a sacred part of the rocky wilderness of Saudi Arabia that once supported a myriad of native flora and fauna, including the elusive Arabian leopard. Upon full completion in 2024, Sharaan will have 40 rooms, three villas, and 14 pavilions sprawling an area of over a million square feet. It is an ode to Nabatean design and to the sandstone rock sculptures of the Sharaan Nature Reserve, considered millions of years old. Reminiscent of the principles of Frank Lloyd Wright, who once said, “Nature is God of the architect,” Nouvel’s vision seeks for the architecture to disappear within its surroundings, taking into account every crevice, dip, and curve of the rock to find the most suitable expression for various structural aspects.

To find a starting point in such vastness is hard, but Nouvel started by reading the sky and the horizon, and led his team to imagine the resort’s possibilities with the existing rock formations, allowing as much natural light to filter through the space as possible so visitors could be completely at one with nature. “Often, we have the impression that the desert contains nothing, but it’s very mysterious and there are a lot more things deep within, many aspects to discover in the light and many variations with the wind. I need to construct architecture within that context.”

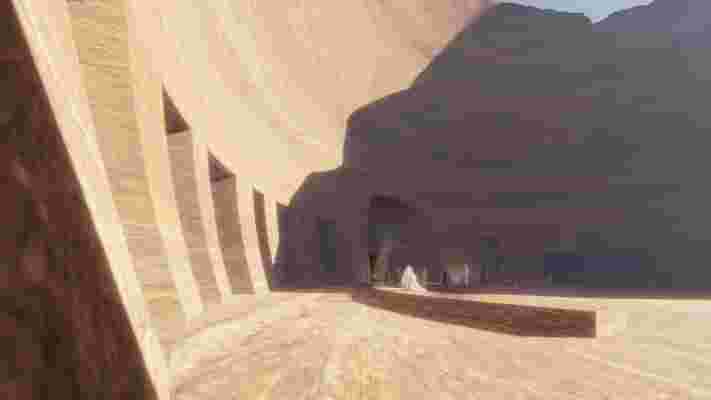

A view inside the grand hall of the resort.

AlUla, an area considered sacred and highly protected by the royal family, includes Saudi Arabia’s first UNESCO World Heritage site of Hegra, the Nabatean kingdom’s southernmost and largest settlement after Petra. “Petra echoes the same thing [as AlUla],” says Nouvel. “It is also architecture carved in the rock and has the same attitude [of reconciling heritage to the landscape].”

Located 200 miles north of Medina, AlUla is considered a place of extraordinary human and natural heritage. It is here that visitors can find Wadi Al-Qura (the Valley of Villages), an oasis valley sheltered by sandstone mountains that created an ideal environment for many civilizations, including the Dedanites, Lihyanites, Nabataeans, and Romans.

Nouvel notes that the meshrabiyeh patterns (pictured) allow natural light to enter a space while not overwhelming it with heat.

Sharaan by Jean Nouvel will add to the layers of allure in this part of Saudi Arabia, which already has new accommodations being built and new tours of key heritage sites being added. By 2035, the area hopes to host 2 million visitors annually.

With a keen eye for detail, Nouvel explains how the precise rock formations of the Sharaan Nature Reserve, which “was already architecture, sculpted by the wind,” led him to envision the way the resort would unfold, using solids, hollows, and lattice-like moucharaby patterns.

He and his team created a hollow sphere in the desert that serves as the resort’s ceilingless grand patio, flooded by natural light. From this central point, guests stroll and enjoy the surroundings, and views open to lobbies and rooms. To give guests the feeling of immense space, a grand hall runs through the hotel with a ceiling lattice of light. Room walls follow the natural undulations of unique rock formations, and the resort architecture, including awnings and balconies, is enriched by aspects already present.

A view of the open communal patio at Sharaan.

“The architectural motifs should not look like an attempt, but be enriched by the things already there, and not do any things that are not part of the natural rock motif,” he explains. “If you’re making a window, for example, you need to see what the reason is for that space. It’s a very precise, very subtle vocabulary, and a play on what exists and what will exist, because there will be some things that are constructed.”

In this sense, there is a dimension of discovery in all the rooms, a departure from what visitors would find in a standard hotel. Nouvel emphasizes the perennially mysterious nature of rock with its myriad of hidden possibilities: “Each room has its own theme and will play with light, windows, meshrabiyeh. All these elements create a new atmosphere.” With a sense of openness that mimics the feeling of the desert, the resort anchors visitors with public spaces that draw attention to the lifestyle of desert living, through rain or shine, amid various colors and transformations of the desert rock by day and night.

His approach is both curatorial and museographical, drawing attention to the sensory nature of living in the desert, inviting visitors to feel the hardness of the rock as well the modern contrasting softness of sofas and armchairs. “When it comes to chiseling the rock, it is to live in, not to construct a building. The rock demonstrates a natural motif and an expression that is quite unique; it invites us to stay in that space.”

Drawing on emission-free power and committed to sustainability, the resort will have subtle details, including finely chopped stones adoring balconies and natural terraces that highlight the unique granularity of each rock wall. Nouvel notes that the resort will also protect and preserve the native desert flora in many ways through its terrace and communal gardens.

The Nabateans were known for their excellence in constructing wells and were resourceful in using materials like rock and stones to build structures essential to everyday living. Nouvel’s vision for Sharaan follows a similar path. A grand elevator runs through the resort vertically in what Nouvel calls a “light well.” “And then you’re on a completely different scale because when you glance 80 meters [262 feet] up, you see the sky,” he says. “Light plays an enormous role in this hotel, to give it the feeling of a natural space,” he notes, adding that there is little artificial ventilation in the resort.

At every moment, Sharaan seeks to unite visitors with the surrounding landscape.

Once the eye scans the rock, Nouvel says, it will find geometric patterns, rhythms, and certain colors in its striations: “This is similar to how we sometimes scan the clouds and see patterns that we have been searching for a long time; we look at the rock for all these things.”

With a new technique created to celebrate the genius of Nabatean design—including the delicate meshrabiyeh which delicately filters natural light into rooms—Nouvel aims to give a modern take on millennia-old ways of living. It was also important for him to not make visitors feel claustrophobic within the chasm of surrounding rocks. “We need to find the sky…this is a very important dimension for me,” he says of allowing natural light to filter through seamlessly in various ways. Ultimately, what drew him to design a resort in this part of the world were the sculpted rock formations. “I’ve never seen anything with this amount of precision before,” he notes, adding that because these rocks “were already architecture,” he had no notion of carving or cutting the rock to do his bidding.

“We simply elevated the motifs we found: the rock is profound. We wanted to create a total harmony with the surroundings.” In this sense, “it is demanding,” says Nouvel of the architecture. “Because it is constructed in the landscape as it is, that is an enormous responsibility. But it is also an act of love, to absolutely respect the conditions of such a context.”