Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Tugendhat House is the subject of a documentary film at the New York Jewish Film Festival

In “The Athens Charter,” a manifesto on functionalism and modern architecture, Le Corbusier wrote, “Who but an architect would know what is best for humans?” To him, the architect was the authority on living. But Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier’s contemporary and collaborator, saw it the other way around: Modern man was demanding modern architecture.

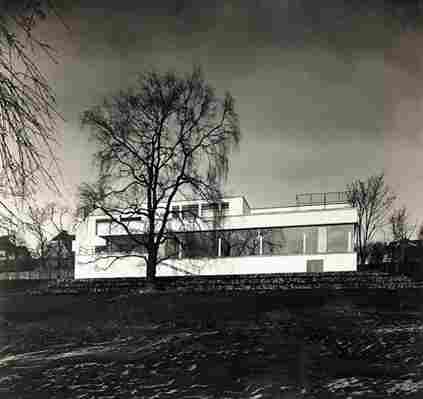

Out of this theory emerged the Tugendhat House, a striking glass home that Mies erected in Brno, Czech Republic, in accordance with the taste of design-loving Jewish factory owners Grete and Fritz Tugendhat. The three-story villa featured a glass façade with sliding walls, a travertine floor, chrome banisters, and a single onyx wall in the main living area that changed in color and translucency, depending on the sunlight. The decorative scheme was equally spare, showcasing furnishings Mies created for the project with interior designer Lilly Reich, some of which—such as the Brno chair—became hallmarks of his oeuvre.

With such a distinct and innovative look, the house has become a modernist monument, now the subject of Dieter Reifarth’s documentary film The Tugendhat House , premiering in the U.S. on Wednesday in a screening presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and The Jewish Museum as part of the New York Jewish Film Festival.

“We have a house here which is perhaps the last total work of architectural art of the kind we are familiar with from the turn of the last century,” says German art historian Wolf Tegethoff in the film. “The architect planned the building from the basic structure down to the carpet and the drapes.”

By speaking with remaining Tugendhats who spent parts of their childhood in the home as well as art and architecture historians who have studied it, the filmmaker traces the narrative of one house—from its conception, rooted in functionalism, and the domestic life that briefly unfolded there, to the displacement of the Tugendhat family during the Nazi occupation and the house’s various incarnations that followed. After being confiscated by the Gestapo in 1939, it served as apartments, a ballet school, a therapy site for scoliosis patients, and the location in which Václav Klaus and Vladimír Mečiar negotiated the secession of Czechoslovakia in 1993. As inhabitants came and went, elements of the historic home were added, removed, and modified.

Now a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site, Tugendhat has been restored to a state that resembles its original and opened to the public. But, as many of those interviewed for the film express, the restoration left something to be desired—it feels, to them, like an empty model home. And so perhaps, by rounding up such spirited first hand accounts and archival footage of the legendary structure, The Tugendhat House preserves this relic of Mies’s modernist vision in a way that the physical building no longer can.

The Tugendhat House premieres Wednesday, January 28, at 6 in the Walter Reade Theater at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, 165 West 65th Street, New York; filmlincom