Never-Before-Seen Film of 7 Frank Lloyd Wright Houses

The University of Southern California recently released a newly digitized collection of about 1,300 slides of some of the most iconic buildings in the American West, designed by the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra . The photos were taken by architects Pierre Koenig , known for his own work in Southern California, including Case Study Houses 21 and 22, and Fritz Block, who owned a color-slide company in Hollywood and shot many private residences in the same area.

In honor of the celebrated architect's upcoming 150th birthday, AD has combed through the archive to bring you a never-before-seen look at some of Wright’s masterpieces from the Golden State and the surrounding area, all culled from Block’s collection. The images, taken between the 1920s and '40s, offer a dreamy look at some of Wright’s greatest architectural accomplishments, seen from an insider’s point of view. You can also view the full archive here .

Shown: With a filmography that includes Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks , the Ennis House is one of Wright's best-known works. Completed in 1924 for menswear store owners Charles and Mabel Ennis, the Los Angeles home is famous for its distinctive Mayan Revival style.

Precast concrete blocks, each designed with a Greek key relief, make up both the exterior and interior of the home. Now owned by financier Ronald Burke, the house is open to the public 12 days a year thanks to a legal stipulation from the Los Angeles Conservancy.

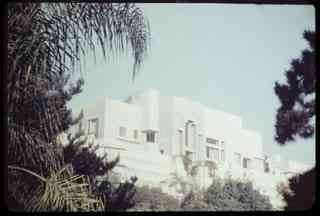

The Aline Barnsdall Hollyhock House, Wright’s first project in Los Angeles, was named for the oil heiress who called it home and for the stylized hollyhocks (the homeowner’s favorite flower) that grew on its exterior. Completed in 1921, the residence was conceived in a Mayan Revival style with input from Wright's son Lloyd, as well as his assistant Rudolph Schindler.

The home wraps around a central courtyard, an unconventional layout for its time, with split-level terraces that segue into the interior. The property also includes a complex waterway system, wherein water circulates through a garden pool, a moat, and a fountain.

One of Wright's Usonian homes (fulfilling his vision for the new American dwelling), the Sidney Bazett House, was finished in 1940 for its eponymous financier owner and his wife Louise. Laid out in an L-shape, the Hillsborough, California, home is marked by hexagonal angles and Wright's signature low, flat construction.

Jean Hanna, a previous client of Wright's, consulted with the Bazetts on their personal criteria for a new home during the initial planning for the site. Among their requirements were a single-story layout, convenient access to outdoor spaces, and an open-plan living and dining space, shown here.

The Millard House, the first of Wright’s Textile Block Houses, so named for textured concrete walls that resemble brocade, dates from 1923. The home was commissioned by Alice Millard, a rare-book dealer, and sits tucked into a ravine in Pasadena, California.

On the first floor of the home were a kitchen, dining room, and servants' quarters. The second floor, shown here, included a two-story living room overlooked by a balcony off the third-floor master bedroom. The concrete walls, while rough on the outside, were smooth on the interior.

Built in 1923, the Storer House is another of Wright’s Textile Block Houses, which he designed to fit seamlessly into its hillside Los Angeles setting. Commissioned by homeopathic physician John Storer, the house prominently features Mayan style influences and a lush landscape devised by Wright’s son.

A wraparound porch with panoramic views of Los Angeles is one of the defining features of Wright’s Sturges House, built in 1939. The Usonian home—made with concrete, brick, and redwood—is also known for its cantilevered construction, which allows it to nestle into a hillside.

Commissioned by George D. Sturges, the one-story home is located in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. Designed with the same linearity as the exterior, the interior features an open floor plan to maximize space in the relatively small home.

Completed in 1937, Taliesin West was Wright’s winter home and studio in Scottsdale, Arizona, where the architect lived until his death in 1959. The house was composed of local rocks that fit into wooden forms and were then set using concrete, integrating the home into its landscape.

Shown here is Wright’s study at Taliesin West, which incorporated a roof of translucent canvas, later replaced by more durable plastic. Using natural light to illuminate a home’s interior was a Wright trademark.