Rocky Mountain Resolution

View Slideshow

I wanted a house where my family and friends would enjoy being," Fred H. Bartlit, Jr., says of his year-and-a-half-old clifftop aerie in Castle Rock, Colorado. "This isn't a contest; we're not competing with anybody. I didn't want the word impressive ever to be used."

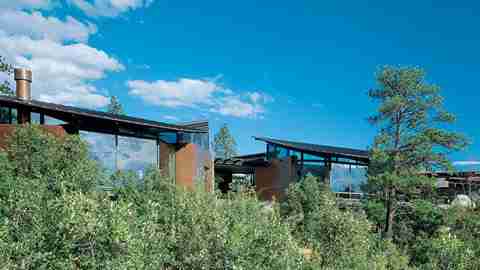

But in life, it seems, we never get exactly what we want. The house, designed by David Lake, Ted Flato and Karla Green, of Lake/Flato Architects of San Antonio, is an impressive structure on an equally impressive site. The eighteen-room, 6,500-square-foot residence is an unusual composition of angular steel-and-glass pavilions backed by an earthwork formed by bedrooms roofed with sod. It might elicit as many compliments as the Front Range peaks it frames.

While they may have underestimated the impact of the house on others, through an extraordinarily close collaboration with Lake and their interior designers—Alex Jordan and Dan Smieszny, of Gregga Jordan Smieszny in Chicago—Fred Bartlit and his wife, Jana, did get everything else that they wanted. Fred Bartlit describes his marriage as "a unique two-person team—we do everything together." This includes work as well as play: Jana Bartlit often accompanies her husband when he makes appearances as a trial lawyer in courts in the United States and Europe. "We're always under stress," he says, "seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day." So the house was envisioned as a kind of retreat. The architect's goal was to balance protection and openness, security and space, while maintaining a low profile on a high-profile piece of land.

The Bartlits arrived on their ridge in Castle Rock, sixty-four hundred feet above sea level, after many years of living on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago. They loved their Bruce Gregga-designed apartment there, but they felt that there might be more to life than what was available in that cold, midwestern city. "We looked everywhere—Santa Fe, Carmel, the usual suspects—before we found this place," Fred Bartlit says.

The residence began humbly, with a pair of photographs. "They showed me a Romanesque loggia, and I said, Well, I don't think that fits the terrain,'" Lake remembers. He countered with an image of a ruined Irish burial cairn where lichen-spotted stone walls interrupted a hill and trailed off like spread fingers into the land. To his surprise, the Bartlits approved, and Lake was emboldened to push his clients even further.

First, he personally selected a site that would take advantage of a swale along the edge of the cliffs, then he returned to Texas to give form to the house that would crown it. Working subtractively on a clay model, Lake and his team roughed out what he remembers with a laugh as a long-shot scheme inspired by the contours of the site, that mossy Irish cairn and the rusty minehead shacks common in the area. "They said they loved it, and I said, Oh my God, now we have to figure out how to do this.'"

The finished house reveals none of Lake's initial anxiety. One approaches it by traversing a prairie-topped mesa toward stands of scrub oak and ponderosa pine that mark the edge of the 116-foot-high cliffs. The house's sloping formal entrance emphasizes the proximity of the drop. It was conceived as a kind of conceptual watercourse, Lake says, a dry arroyo that passes through the house before emptying into the quarrylike pool carved into the swale on the precipice. The dramatic entrance also presents visitors with a concentrated version of the architect's palette: the slightly battered retaining walls of stone and granite, the light copper panels taking their natural patina, the clean dark-bronze-colored steel and the insulated glass tinted with a hint of green.

The entrance ravine also helps to divide the house into its two functional zones. To the right, one passes beneath the elevated windows of the master bedroom. Containing the kitchen, an office and a family room, this section of the house allows for cliff-dwelling in modern-day comfort. The loosely connected pavilions that sprawl along a gallery to the left of the entrance shelter the more public areas of the house—the dining room and a formal living room. Nearby are a pair of spacious outdoor terraces. Light is introduced to the gallery by two landscaped atria; on the uphill side, the two sod-roofed guest bedrooms, the garage and the staff quarters buttress the hill. The garage leads into yet another planted atrium and has an eye-level window with a view to the east. On the opposite side of the gallery, looking out toward the mountains and the light, the public spaces take wing.

The interiors draw their cues from the same logic: the contrast between the bunkers in the hill and the glass pavilions hanging over it. "When you're in the hill and of the hill, you're on stone, with stone," Lake says, describing the walls and floors. "When you're out in the pavilions, you're floating on wood." Lake notes that he and the interior designers worked hard to find other ways to balance the natural energies of the house, to keep its eccentricity in check: "How do you make the rooms as quiet as possible despite their very active geometry? How do you keep order in a highly disorderly plan?"

One strategy was to continue the house-as-reinhabited-ruin theme that was David Lake's initial inspiration. "We introduced elements that became sculptural pieces within the rooms," explains Alex Jordan. "By contrasting the furniture with the architecture, we made it stronger." And they kept it comfortable and calm—two other items on Fred Bartlit's almost perfectly realized wish list: "I wanted a sexy, sybaritic house," he says, "but I also wanted peace."