Rural Echoes in Malibu

View Slideshow

Growing up in rural quebec, Richard Landry spent the summers playing in an old timber barn on a neighboring farm when he wasn't helping out in his father's carpentry workshop. Cows walked through the yard, and his world was so remote from the rest of North America that he spoke nothing but French until he left home at twenty to study in Montreal. Those memories were put away during his years at architecture school, where modernism reigned; and the rapid expansion of his Los Angeles–based architectural practice, designing residences around the world, has left him little time to dream. But now Landry has made time to build a house for himself and his partner in the Malibu hills, and the result is infused with the timeless spirit of the Canadian countryside.

The saxophonist Kenny G, for whom Landry designed an English manor house in Seattle (see Architectural Digest, August 1997), showed them a site he owned, but its location deep in a canyon meant that construction could be prohibitively expensive. On the drive back to the coast highway, they saw another plot for sale and made an offer. A steep grassy incline of eleven acres, bordered by a canyon and state parkland, with access to riding trails and a view of the ocean, it seemed ideal in every way but one: The California Coastal Commission had ruled that it was subject to flooding. "They told us we couldn't build there, even though the ground dropped away on every side," remembers Landry. "But as soon as they came to inspect the site, they realized their maps were inaccurately drawn and waived their objections." He secured approval for a 4,600-square-foot masonry house with a standing-seam metal roof, "silos" to house the baths at either side and a pergola of Douglas fir to shade expansive south-facing windows. Old wood and handcrafted elements would line this functional shell.

Revisiting his childhood home, Landry discovered that the barns in which he had once played were being replaced by fire-resistant metal sheds that were easier to maintain. For farmers, practicality outweighed nostalgia, and they were eager to give away decaying timbers in order to clear the ground for new construction. Landry, his partner and his brother located five decrepit structures, and they selected two that had never been painted and had weathered to a silvery gray. "We measured and numbered every beam, bracket and length of siding and had them trucked to L.A.," Landry recalls. "We had to decide how to use each piece. I could have ordered more, but I wanted to use the old timber with restraint, not make a literal re-creation of a barn."

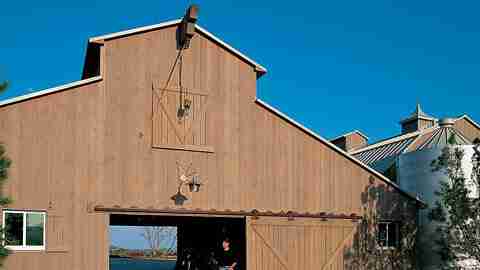

In contrast with new houses that dominate hilltops and appear sadly out of place, Landry's is rooted in the land and seems likely to age gracefully. The entire property is full of references to the traditional forms of farm buildings— from what appears to be a water tank of corrugated aluminum but is actually the pool to a garage whose opening serves as a formal entrance to the forecourt and was inspired by a double crib barn. The loose timbers that carry the driveway over a stream rattle beneath a car's wheels in the same way as do the covered bridges of the Northeast. These features, and the stable for the owners' horses, build expectations that the house fulfills.

"When I design for others, I try not to impose my ideas, but here we wanted to have fun and not worry about resale value," explains Landry. The gambrel roof, with its lantern and cupolas and the canopies over the front and rear porches, and the two "silos," with their sheet-metal skin, were inspired by the rural vernacular. The house steps down the slope, and its rooms flank a lofty space that contains the living areas. This great room is treated as an interior court, overlooked by a gallery that links the wings and by openings to the study and the master bedroom. Old handhewn beams support the pitched vault, and the pergola, visible through the glass doors, appears to be an organic extension of the interior.

There was no compromise on quality. Load-bearing walls, which are mostly solid to the north and open to the south, are composed of split-face concrete blocks. Poured with two complementary colors, they have the texture and subtle tonalities of stone, outside and in. Four varied hues were mixed into a stain for the concrete floor, and the brownish finish echoes the pecan boards upstairs. The drywall was rubbed with beeswax, giving it a parchment tone, and the raw fir beams outside were washed with gray to anticipate weathering. As a result, the house has a glow that is usually attained only with age, and yet, since none of the surfaces were painted, maintenance should be limited to renewing the sealants.

The Canadian barn is a constant presence throughout the house. Dilapidated posts at the foot of the stairs have the impact of sculpture. Siding finds new uses as doors that conceal the stereo equipment and pantry, as shutters suspended from rusted-steel tracks and as massive entrance doors mounted on hammered-metal hinges and pins that Landry designed. Horse yokes serve as door pulls. The spirit of place is evoked in the steel picket fence that forms a balustrade and in the steel plate that has been turned into a cutout frieze of cattails—which flourish in the marshes of Quebec—at the edge of the gallery. The architect sketched the design on a roll of paper and scanned it to produce a computer disk that guided the plasma beam as it cut the steel.

Serendipity was also a factor in the design. Searching for rare patterns of marble in small stone yards, Landry spotted a hunk of greenish granite, the discarded remnant of an order placed by the Getty Center for its gardens. The supplier was happy to give it away, and the architect had its top hollowed out as a washbasin for one of the baths.

In designing a house that is a collage of old and new, it's important to know when to stop. Landry has layered the spaces to achieve a sense of intimacy without clutter, and he has woven together colors and patterns with skill and subtlety. Simplicity and exuberance are harmoniously balanced, and the eye is drawn out to the natural beauty of hills and ocean. Above all, the architect has fulfilled his dream of creating a retreat that taps his emotions. "For me, it goes beyond a house," he says. "It brings back memories of childhood and touches my senses and soul."