The Aspen Mountain Club

View Slideshow

We wanted a european-style club to enhance the skiing experience," says Paula Crown, of the Crown family, the Aspen Skiing Company's major shareholder. "We're all victims of velocity—with e-mail and cell phones—so a place where people could unwind among friends with a great lunch, a book or a game of backgammon seemed ideal." Welcome to the Aspen Mountain Club, which opened in February. Perched atop Aspen Mountain at 11,212 feet, it's almost high enough to touch the sky.

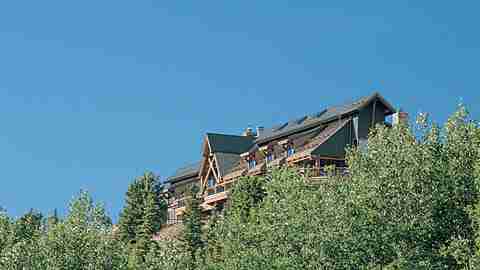

"Upstairs," as some people refer to the club, is a fifteen minute gondola ride from downtown Aspen. The club is a short walk from the gondola station, through a flurry of skiers poised for the pistes and a phalanx of skis propped outside the Sundeck, a new building by architect Larry Yaw, of the firm Cottle Graybeal Yaw. The club actually occupies one wing of the Sundeck, which also houses a public restaurant. The entire building replaced the original warming hut designed in the forties by Fritz Benedict, Aspen's architectural founding father, and Herbert Bayer, of Bauhaus fame.

With wood siding, a patinated-copper roof and a base of native stone, Yaw's structure echoes its remote summit location, European mountain shelters and Aspen's illustrious mining heritage. (At one time Aspen was the largest producer of silver in North America.) A notable twenty-first-century aspect of the Sundeck is that it is one of only ten buildings in the country to receive environmental certification through the U.S. Green Building Council's LEED program, earning stars for, among other features, its use of low-toxicity paints and glues to protect indoor air quality. "We wanted to be in the forefront on issues relating to the environment," says Crown.

Discreetly placed at the far end of the Sundeck's porch is the door to the Aspen Mountain Club. Step through it, and the rawhide West ends. The small entrance hall instantly sets the scene with textured plaster walls painted a soft salmon, printed linen draperies and an antique pearwood commode. "I wanted to blend European and American elements that were suitable for a contemporary Colorado ski resort, without being too alpine,' " says David Easton, who designed the interiors. "The overall effect should give people a sense of being away but, at the same time, the feeling of being at home."

The premise of the club was also to create an athletic venue by offering lots of sports and outdoor activities. There is reciprocal membership with the Eagle's Club in Gstaad, the Corviglia Club in St. Moritz and the Game Creek Club in Vail. The biggest events center around skiing, with races for all ages and abilities. In summer the club organizes hikes, barbecues and off mountain activities such as golf and tennis tournaments. It is also available to the community for nonprofit fundraisers or a moonlit shebang for one hundred. In the "Republic of Aspen," where the idea of private clubs still raises hackles in some circles, accessibility is a plus.

The day-to-day business of the club, however, from first lift up to last lift down, is the utmost tender care and feeding of the 275-plus members. Some perks currently offered are two lifetime ski passes and a locker, featuring individual ski boot warmers, at the base of Aspen Mountain. Unfailing service being the modus operandi, it's no accident that the first person one sees at the club is the concierge. No request is beyond the pale—massages, baby-sitters or airline or dinner reservations.

The club's dining room, living room, small bar and dining deck all have dazzling mountain panoramas and/or views of skiers coming off the lift. Opposite the concierge—just before the tiny room with the fax and the computer for e-mail and stock quotes—the mudroom awaits. Cubbyholes contain the Aspen Mountain Club wool scuffs, made by Sorel (green for "ladies," blue for "gentlemen"). "I love the slippers because I can take off my boots and give my feet a rest," says founding member Evelyn Lauder, who cross-country skis with her husband, Leonard, on Richmond Ridge. "The slippers make everybody feel at home."

David Easton's mission entailed more than just creating a homey nest out of 7,000 square feet. It is, after all, a club. "Guests move in and out of a club; you can challenge them with some boldness because they don't have to live with it twenty-four hours a day," says the designer. "You're also solving problems for one hundred people as opposed to, say, two to six in a house, and that means finding what's functional and comfortable for large numbers."

He also needed to translate the general goal of "European style" into something tangible. "I looked for traditional pieces that I could edit to relate to a modern Aspen lodge," says Easton, who brought in pottery from Italy and fabrics from Salzburg. "To me, a ski lodge is a provincial wood building, and provincial means country elegance." "It has the feeling of a Swiss refuge," observes Eric Calderon, vice president and general manager of The Little Nell, which operates the club. "It's a place where you seek shelter from the elements that's comfortable and welcoming but not too plush and sumptuous." As Easton, who admits he doesn't ski or do any exercise, succinctly puts it: "Nothing too ritzy."

The living room is a warm and inviting space with sofas upholstered in textured linens, wood chairs with cushions, shelves filled with books and board games, and several phones. (There is even a private phone room with a steel door.) The focal point of the room is a floor-to-ceiling stone fireplace. "I might go to the club every day, but I don't always eat lunch," says Jill St. John, charter member with her husband, actor Robert Wagner. "Sometimes on a cold morning I'll warm up for fifteen minutes with a cup of hot chocolate by the fire and read the papers."

"The living room has a sense of physical and visual comfort that puts people at ease," says Easton, who opted for ivory walls and persimmon draperies. "The furniture is arranged in a way that isn't stiff; you can move the chairs around as you would in your own house."

The dining room's generous windows frame the tips of Aspen's famous summits: Maroon Bells, the Highlands and Mount Hayden. An adjoining deck where you can eat takes you even closer to them. "Respecting the vistas was key," says Easton, who felt the décor should complement the architecture and the site. "In all the rooms, you want to look out."

In the center of the dining room is a circle of curved banquettes, above which is a gunmetal steel chandelier suspended from a sunburst medallion painted by Anne Camp Thomas, set into the pineboard ceiling. "Most of the kick comes from textures—the cornhusk-yellow banquette wool, the crewelwork on the pillows and draperies, the Portuguese needlepoint carpet, the different woods—rather than a strong decorative color," says Easton. "I felt the envelope had to be neutral to suit the room's many uses."

Just off the living room is a small bar with a stone fireplace and a large banquette under the window. One can sit at the bar or on Isle of Orkney-style chairs at a table and order from the bar menu. For absolute dining privacy, members can descend via a spiral staircase to the cave, or wine cellar. The intimate space has an etched-and-stained-concrete floor, a big stone fireplace, two handmade wood tables that easily seat ten and an early eighteenth-century steel chandelier.

The powder room around the corner, however, breaks ranks with the club's décor. It's painted bright red. Why? Just for the hell of it. "Architecture and decoration are emotive things, and sometimes you have to stop thinking and just go for it," says David Easton. "I think you have to say that about life."