The Improbable Story on How the Martin Luther King Jr. Monument Came to Be

A decade ago, there was a design competition to create the Martin Luther King Jr. monument on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The ultimate goal was to select one idea from 900 designs to honor the trailblazing civil rights leader in a historic monument. It was spearheaded and sponsored by the Memorial Foundation , an organization that helped fund the $120 million project that took over a decade to create and opened in 2011.

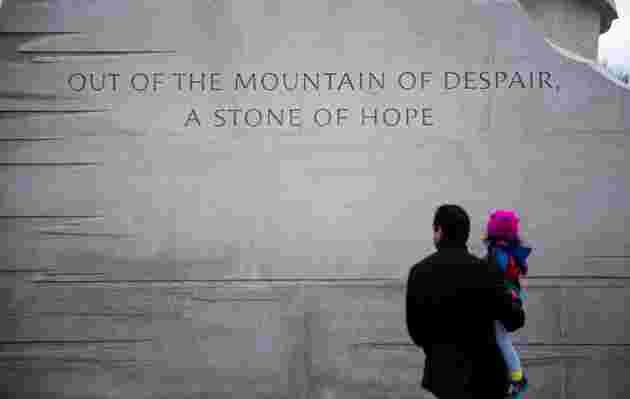

The monument is probably the most iconic of all monuments that honor the civil rights leader, who led a peaceful change with his “I Have A Dream” speech, fighting for the freedom of others in a time of intense struggle. Though there are many quotes in the sprawling four-acre memorial, one of them, perhaps, commands the most attention. “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.” It not only refers to Dr. King’s speech, but within the monument there are also two large stones that look as if a mountain has split in two, allowing viewers to walk through the separation.

There were many people involved in the 10-year process, including Marshall Purnell of D+P Partners Architects , a D.C.-based firm that he co-led for 35 years. He was the first African American president of the American Institute of Architects, an organization that didn’t allow Black architects to join as members until 1923. He was also the president of the National Organization of Minority Architects. Some of the most notable projects from his four-decade career include the Washington Convention Center, the Washington National Airport, and Pepco’s headquarters.

Purnell speaks to AD about working on the project, the power of quotes, and the struggles to complete this memorial.

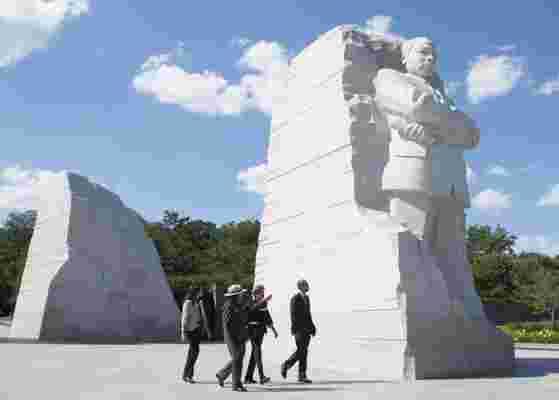

U.S. President Barack Obama walks past the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in 2015.

Architectural Digest : What is the background of how the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial came to be?

Marshall Purnell: It was an international design competition sponsored by the Memorial Foundation. The foundation was started by some of Dr. King’s fraternity brothers from Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., who called me out of the blue. They asked if we wanted to do a memorial for Dr. King on the National Mall. The Roma Design Group [now called Roma Collaborative], based in San Francisco, won the competition. We formed a joint venture with Roma and got all of their designs approved by the Commission of Fine Arts, the National Capital Planning Commission, and the National Park Service. This formal review process took two years.

How did the initial drawings turn into its final design?

Initially, there wasn’t going to be a sculpture there; the whole idea of the memorial was to use Dr. King’s words. We felt Dr. King wasn’t about his personal image. His personality wasn’t one of, “Look at me.” He was a leader who many listened to. But the Memorial Foundation insisted: “We need to have an image of Dr. King.” They were the ones in charge, so we agreed.

What is the most important part of this memorial, in your eyes?

The wall of quotes. All of those quotes were our design work on the granite. We gave them four or five quotes, and they went with 80% of the ones we suggested.

How do you feel about the specific location of the memorial in the National Mall, on the northwest corner of the Tidal Basin?

It’s a gorgeous site and the perfect location for it. I thought it needed to be far away from other structures to be more contemplative, so you could stand there, read the quotes, and not hear the traffic or see other people.

A man and child stand near the MLK Jr. Memorial, reading the quote, “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.”

How did it feel to work on the design alongside the Roma Collaborative ?

When we got the opportunity to do it, I thought, “I would have done it for free, I can’t believe they’re paying me to do this.” It’s one of the best projects I’ve ever done because it was about Dr. King.

How rocky did it get, as a process? Ten years is a long time to work on a monument.

It got to the point where the Memorial Foundation wasn’t happy with us because we didn’t side with them when they had disagreements with the National Park Service. So, we came up with something everyone could live with. Next thing we know, we were fired, but it still got built, so all’s well that ends well. A lot of people thought us getting cut out at the last minute was bad, but that didn’t stop it from being built. I thought: “This is not about me.”

When you finally did see the completed memorial, how did you feel?

The biggest feeling was when I knew it was going to happen—when it finally got all its approvals. There were some people who didn’t want Dr. King on the Mall, period. But when we actually got it all approved, and it looked like it was going to happen, I felt like we did it. I was thrilled to see it all come together.