UVA’s New Memorial to Enslaved Laborers Confronts the School’s History

Between 1817 and 1865, approximately 4,000 enslaved people worked on the campus at the Thomas Jefferson–founded University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. Both owned and rented by the university, these forced laborers were responsible for the creation and maintenance of the school’s lauded grounds, including the UNESCO Heritage–protected Rotunda that was designed by Jefferson, an architect, the third United States president, and a slave owner. Catalyzed in 2010 by a group of students who assembled themselves to raise awareness about the history of slavery at UVA, the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers honors the community of African Americans who built and maintained the lives of the student, faculty, and staff at the very campus where it is sited. Designed by a team of collaborators that includes architecture firm Höweler + Yoon , designer and historian Dr. Mabel O. Wilson, Gregg Bleam Landscape Architect , community facilitator Dr. Frank Dukes, and artist Eto Otitigbe, the circular memorial is intentionally unfinished in its inscriptions, representing the work still to be done to combat anti-Black racism.

Aerial view of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers and UVA Grounds.

“This memorial has the responsibility to acknowledge history, to honor the lives of the enslaved, and bring them the dignity and humanity that was taken away from them by the dehumanizing act of slavery, but also to be a space that acknowledges that the work of addressing the issues of race in America is not finished,” Meejin Yoon, cofounding principal of Höweler + Yoon and dean of architecture at Cornell University, tells AD . Two years after the aforementioned students organized a competition for a memorial for the laborers enslaved at their college, UVA formed the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University (PCSU) to research its history of slavery and explore ways to recognize the contributions of enslaved people to the institution. In 2016 the school commissioned the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, eventually sited on the “Triangle of Grass,” a piece of the UNESCO World Heritage–preserved grounds just east of the Rotunda. Here, the landscape—including UVA’s iconic serpentine walls—was originally designed to hide views of enslaved workers on campus.

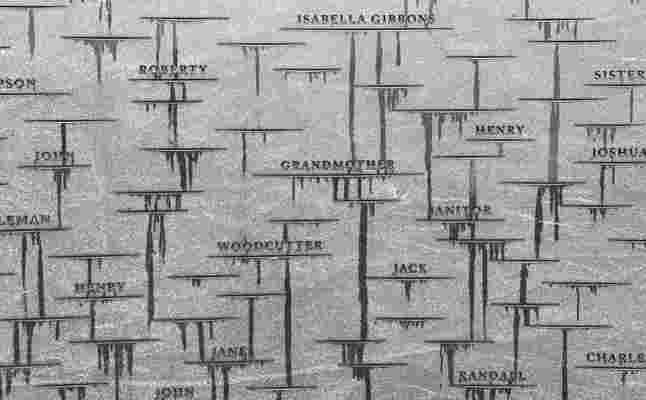

The memorial is created of local granite, hewn in several ways for a variety of textural effects. The 80-foot-diameter memorial features a central gathering space, a water table with a timeline honoring the enslaved people at UVA (beginning in 1619 with the first arrival of enslaved Africans to Virginia), a memory wall of their names and marks, and a portrait by Otitigbe of Isabella Gibbons, a formerly enslaved person who was later a teacher in Charlottesville. Each design element is bathed in layers of meaning: Water references African libation rituals, baptism, the Middle Passage, and river routes to liberation; the textured granite represents both the physical suffering and enduring spirit of enslaved people; its ring shape is a reference to the African liberation “ring shout” dance and meant to evoke a sheltering embrace.

Visitors at the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at UVA.

In addition to revealing slavery’s past, the memorial articulates the enduring segregation and inequality that resulted—“the centrality of slavery to America and American economics, and also the violence inherent in jumpstarting the nation by maintaining slavery,” says Wilson—and allows a place for descendants to mourn, contemplate, and be acknowledged. Yoon notes how difficult it was for the team to trace the history of slavery at the school due to inefficient record-keeping. Of the 4,000 known enslaved community members at UVA, historians were only able to find full names for 578 and nameless kinship relationships for another 311. These forgotten, buried, and lost histories were crucial to the creation of the memorial. Their names will be added as they are uncovered.

Though its official dedication ceremony in April was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Memorial for Enslaved Laborers has spontaneously become a place for gathering and contemplation during nationwide protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement since the killing of George Floyd in late May. Seeing engagement with the memorial is proof of a successful community engagement process, says Wilson. “Your constituents will challenge you and if you make it a productive dialogue, they will realize that your work has listened to them. That’s invaluable,” she explains. “You need people to do memory work. There are statues whose values are no longer reflective of the community. We heard what people wanted.”

Detail shot of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers inner wall, with names and memory marks honoring members of UVA’s enslaved community, after the rain.

What the people wanted was a multifaceted, contemporary space for mourning, gathering, learning, and understanding. Says Yoon: “The memorial needs to be understood as part of the commemorative landscape of racial justice today, that’s why it should be an ongoing open project.”