Venerable Oxford Library Gets a Modern Makeover

The campus of England’s Oxford University is hardly lacking when it comes to architectural masterpieces. From Nicholas Hawksmoor’s neoclassical Clarendon Building to Arne Jacobsen’s modernist St. Catherine’s College, the prestigious academic institution has a long history of significant commissions that have proved their enduring relevance over many decades, or several centuries, of use. The Weston Library, designed in the 1930s by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, is no exception, and after a $118 million renovation, the storied library has recently reopened its doors to reveal an impressive contemporary upgrade courtesy of the London-based firm Wilkinson Eyre.

Part of Oxford’s Bodleian Library network, the Weston is home to countless rare manuscripts that were in need of modern conservation facilities. In addition, the university wanted to encourage public access, and make the collections more easily available to students and visiting scholars alike.

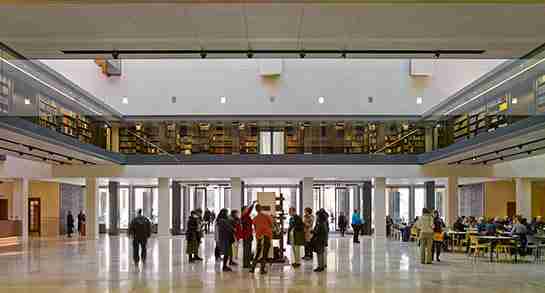

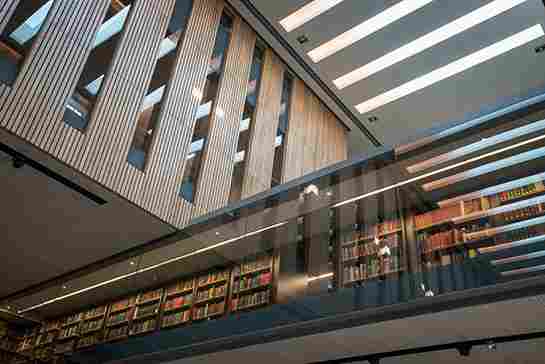

Accordingly, the refurbishment includes seminar rooms and a lecture hall, a café, and new exhibition galleries for public enjoyment. An 11-story bookstack that was formerly at the center of the building—which was originally designed in the shape of a classic university quadrangle—was downsized to make way for upper-level reading rooms and research areas, while the underground stacks were reconfigured to meet modern library standards. The construction materials used throughout stayed true to Scott’s intentions, with stone, timber, and bronze additions mirroring the site’s initial foundations.

Most crucially, Wilkinson Eyre moved the entrance of the library from a back road to the main square, where the building’s new arcaded entryway and restored façade—refitted with 140 tons of salvaged stone—now sit in conversation with Hawksmoor’s Clarendon Building and Sir Christopher Wren’s Sheldonian Theatre.

“The question, of course, was how do you collaborate with the existing architecture without sort of aping it?” says Jim Eyre, director of Wilkinson Eyre, which spent nine years on the project. “I think our work is sympathetic to the existing architecture. The materiality is actually quite close, but there’s also an intentional separation between the new and old, so it’s quite clear what’s what. The two elements are inevitably distinct, but I like to think it feels like a collaboration between the dead architect and the living ones!”