Cass Gilbert

View Slideshow

I sometimes wish I had never built the Woolworth Building because I fear it may be regarded as my only work and you and I both know that whatever it may be in dimension and in certain lines it is after all only a skyscraper." The architect Cass Gilbert wrote these words to his colleague Ralph Adams Cram in 1920 about the building that is generally considered to be his masterpiece. Gilbert was not being falsely modest: When the Woolworth Building was finished in 1913, it was the tallest building in the world, widely acclaimed for the beauty of its Gothic detail and the grace with which it seemed to blend modernist energy and traditional architectural form.

It was all but synonymous with the New York skyline until the Chrysler and Empire State buildings came along in the early 1930s. But its architect never overcame a certain uneasiness about the way in which his lyrical tower got all the attention. What Gilbert wanted most of all was to make civic symbols, and he was never fully convinced that tall commercial buildings were the noblest additions to the cityscape. He didn't like the fact that both he and New York City were better known for the Woolworth Building than for a structure like his U.S. Custom House, an extravagant Beaux Arts palace that is barely more than a tenth the height of the Woolworth but that gives off a spectacular aura of civic grandeur.

Curiously for a man who was the farthest thing imaginable from a proto-Donald Trump, Gilbert's reputation is about to be tied even more to his great skyscraper, sixty-six years after his death. The owners of the landmark building—conscious of the huge demand for housing in lower Manhattan—have announced plans to convert the upper floors of the Woolworth Building into condominium apartments. You can't live in the Empire State Building—at least not yet—but if the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission approves the plans filed by Skidmore, Owings Merrill to redesign the interior of the slender tower section of the Woolworth Building (and add a pair of discreet rooftop penthouses), you will be able to live in what is still, eighty-eight years after its completion, one of the world's iconic skyscrapers.

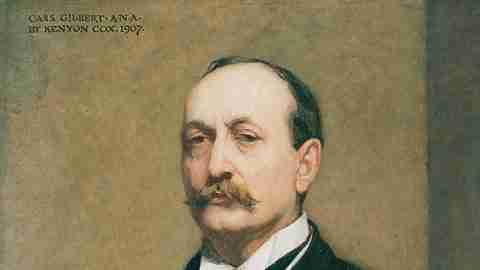

Gilbert would probably have approved, if grudgingly. He embodied a strange combination of pride and pragmatism, and in effect, both of these qualities are reflected in the changes now afoot at the Woolworth. The greatest pleasure of "Inventing the Skyline: the Architecture of Cass Gilbert," the exhibition that is on view at the New-York Historical Society until January 21, 2001 (and that is accompanied by a handsome book of the same title, published by Columbia University Press), is the extent to which it provides an insight into the way the architect thought. Gilbert was formal, stuffy, ambitious, loyal, conservative in the extreme and more than a little prissy. He believed, quite simply, that architecture existed to confer upon institutions, organizations and cities—and, by implication, people—a certain dignity, even nobility. But he believed with equal certainty that an architect's job was to solve problems, and he saw no conflict between these aims. He had an instinctive feel for beauty and composition, but he also sought a balance between form and practical concerns. Gilbert saw a building as something more than an economic entity or a pure shape; to him, architecture was about both of these things, but primarily it was a symbol of a client's aspirations—and a community's.

In this sense Gilbert was one of the great American eclectic architects who filled American cities with lavish Neoclassical and Georgian and Tudor and Gothic and Renaissance banks and clubs and courthouses and libraries and churches and city halls and train stations and houses for the rich. McKim, Mead White, Carrère Hastings, James Gamble Rogers, Delano Aldrich: They were all his peers, a fraternity of architects who had close ties not only to one another but to the business and cultural establishments of cities all around the country, and they took pride in their belief that they were carrying on the great architectural traditions of Western history. They did most of their work around the same time as Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright and the developing modern movement in Europe, but they had no particular interest in modernism. They did not question the order of the world; they believed their mission was to continue it.

The eclectic architects were more inventive than the modernists gave them credit for being, though, and only rarely copied historical precedent directly. McKim, Mead White set a tone of creative reuse of history, and Gilbert, like his colleagues, followed it. Nothing he designed looked precisely like a building from the past; he saw each style as a kind of language, and his goal, we might say, was not so much to memorize Homer as to write new poetry using the vocabulary of ancient Greek. Gilbert and the other eclectic architects cared passionately about monumentality and continuity, and about the notion that cities were places in which great buildings worked together to form a coherent whole.

Gilbert had a narrow view of the world that was typical of his time: He believed that professions were for men—generally white, Protestant men —and professional expertise, like Western cultural history, was invariably to be trusted. His buildings, however, transcended his personal limitations. From the Detroit Public Library to Oberlin College's art museum to the United States Supreme Court building (his last major work, completed just after his death), Gilbert's buildings are masterworks of composition, and they are startlingly fresh. Were he alive today, Gilbert might rant about our continued focus on the Woolworth Building, but "Inventing the Skyline" makes clear how much remains, still, to be learned from looking at this extraordinary tower.

It is a story of a client, Frank W. Woolworth, who made a fortune in five-and-tens and wanted to build a symbol of his corporate power (which he paid for in cash, all $13.5 million of it), and of an architect who found in this commission the perfect blend of his romantic and his pragmatic instincts. Gilbert selected an ambiguous mixture of Belgian and French Gothic as the basic style, since he understood, just as completely as Louis Sullivan did, that the skyscraper had to express verticality if it was to have meaning as a new kind of building form—and what expressed verticality more clearly than the Gothic? And yet he also knew that no cathedral was 792 feet high and contained fifty-five floors of offices, so he had to be inventive.

Gilbert's ideas had actually begun to form several years earlier, when he designed the West Street Building, a few blocks south of the Woolworth. It was his first attempt to design a Gothic skyscraper, and while only a compromised version of it was built (a central tower was omitted, presumably for reasons of cost), its elegance attracted Frank Woolworth and led him to approach Gilbert when he was ready to design his own building. For Woolworth, Gilbert first produced a larger version of the West Street Building, and then, as architect and client worked together, the skyscraper became taller, somewhat sleeker, lighter and thinner in its feeling and more expressive of height.

"Inventing the Skyline" includes several presentation drawings of different versions of the tower, every one of which is stunningly detailed and colored, a world away from the cold computer renderings of today. But more important, they serve as a welcome reminder that no architect, not even Cass Gilbert, developed ideas all at once. The West Street Building and all of the rejected versions of the Woolworth Building were steps in the creative process, every one of them significant. For without them there would have been no masterpiece.