How Paris Became the Arbiter of Modern Architecture and Design

Paris didn’t always leave tourists’ mouths agape with its neoclassical beauty and rhythmic sense of order. As Joan DeJean explains in her engaging new book How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (Bloomsbury, $30), back in the 16th century, the French capital’s streets were magnificently malodorous, overrun with vermin, excrement, and mud. An innocent stroll could result in being splashed with muck by passing carriages or even coming face-to-face with a wolf. Yet by the middle of the 1600s, thanks to Louis XIV—an aesthetic crusader who seemed to eat, sleep, and think style—everything had changed. One’s clothes could still be soiled on walkabouts, but for many visitors the stains were worth it, given what the exponentially improved metropolis had to offer.

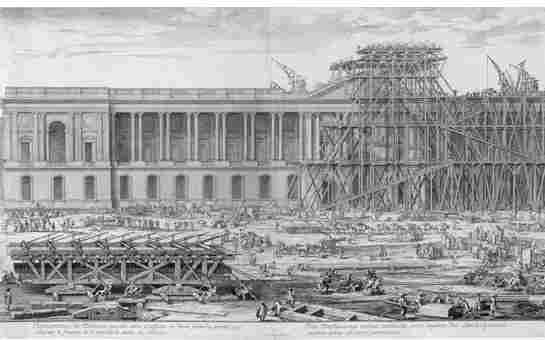

The ardently Francophile author of the witty history The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual—and the Modern Home Began (2010), a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the liveliest presences on the design-lecture circuit, DeJean expertly examines how the French capital went on a binge of self-improvement to become the paradise of everything à la mode. She has skillfully mined archives, museums, manuscript collections, diaries, journals, engravings, and more sources, gathering colorful anecdotes and intriguing visuals that bear witness to her subject’s segue from medieval gloom to future-shock ebullience.

Early travel guides emphasized Paris’s reputation for modernity, from commissioning the most beautiful (and technologically advanced) architecture to the population of aristocratic hostesses who gathered the most influential writers and artists into their orbit. Thousands of newfangled carriages rattled through the arrondissements, carrying their passengers swiftly and with more comfort than the wagons of old—and resulting in stupendous traffic jams, a modern by-product that bedazzled out-of-towners.

The new, improved Paris flickered with uncommon brilliance, too. Lanterns illuminated the streets after dark, creating a midnight-sun effect that encouraged one to venture out in pursuit of nighttime diversions: restaurants, cafés, operas, ballets, and the like. Shop windows were lit as well, an innovative marketing tool that enticed nocturnal wanderers to come back the next morning to purchase what had glittered behind the glass.

Thanks to the French court’s obsessive pursuit of extraordinary hairstyles, extravagant gems, and flamboyant gowns, Paris soon became an unparalleled fashion arbiter; one could arrive from a far-off province in dated finery and return home splendidly and trendily turned out. And if a smartly dressed man decided to swan down the rues and avenues, he risked experiencing another of the capital’s innovations: the filous, thieves who specialized in snatching the costly cloaks and capes known as manteaux. Many filous targeted travelers who were heading to gaze with astonishment upon the wondrous Pont Neuf, or New Bridge, the only bridge in the city that offered views of the skyline—so, as DeJean humorously notes, “if you noticed your cloak was gone, the bridge couldn’t be far.”

One starry-eyed tourist in the 18th century wrote, “All the most original ideas originate in Paris.” That observation might have lost some of its currency today, but as How Paris Became Paris makes abundantly clear, the City of Light has good reason to hold its head high.

How Paris Became Paris ($30) is available now from Bloomsbury .