Language of Home

View Slideshow

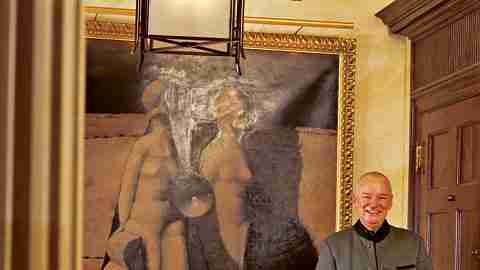

One of the joys of being a truly creative designer is coming up with fresh ideas for new clients. "I don't have any stamp on my work," says Juan Montoya, the Colombian-born, New York-based interior designer. "I don't repeat myself. Every client has different needs and expectations. I tailor my design to each."

A thorough rethinking of a four-bedroom prewar apartment in a prestigious Park Avenue building proves his point. His clients, a busy philanthropist and her real estate developer husband, are young, social and devoted parents to small children.

"The apartment had good bones and some good original detailing. But we still had a lot to do to separate the public rooms and private spaces."

They sought out Montoya after admiring how he had decorated the apartments of three of their friends. Then things got a little complicated. The couple couldn't articulate their style. They used words like "unpredictable," "serene" and "gracious."

"Juan took a long time to understand our taste," says the wife. "We know what it is, but describing it was difficult for us. Juan was able to give us the language to communicate."

As Montoya now explains "They needed a more contemporary sensibility, a sophisticated yet relaxed home for a young family." In other words, they like classic décor that isn't stodgy. They appreciate contemporary materials, 20th-century design and Latin American paintings.

After living in an ultramodern building in Manhattan, the couple wanted a home with a wood-burning fireplace and a family room where the children could play with friends. At the same time, the wife, who serves on the boards of several charities, needed formal rooms to host meetings.

"They needed a more contemporary sensibility, a sophisticated yet relaxed home for a family." They like classic décor that isn't stodgy.

"The apartment had good bones, with continuity between the library, living room and dining room, and some good original detailing," Montoya says. "But we still had a lot to do to separate the public rooms and private spaces." Naturally, much of the makeover is invisible (no one ever notices new wiring, air-conditioning, plumbing or kitchen appliances), but much is also very visible.

The entrance, for example, was a dreary narrow box with five doors (to the elevator, coat closet, living room, entry to the master bedroom and corridor to the children's wing).

Montoya's solution should be in a textbook. "First, I took off the wainscoting, to make the ceiling look taller," he says. "Then I made all the doors match, with dark new paneling and overscale moldings. They look much higher and grander now."

He opened the wall leading to the private quarters and inserted two fluted columns, painted to look like marble, in front of the corridor joining the master bedroom to the children's wing, improving the circulation to the apartment's public and private wings. Behind the columns, he inserted a new powder room with a door disguised with the same trompe l'oeil limestone pattern he had painted on the walls, and he installed a travertine floor interspersed with strips of brown-veined Emperador marble. "The marble simplifies the hall," he says. "The strips create a sharp geometric pattern to define and give character to the space."

With the shell complete, Montoya could then decorate the room in his usual eclectic way, with a 19th-century Danish settee, two small bronze low tables by the artist Philip Laverne, a colorful oil by Victor Matthews and a Spanish colonial-style carved mirror made in Colombia and a Japanese- style lantern, both of his own design. For the final touch, he added a 1920s gilt-bronze console table with a marble top by the noted Parisian metalsmith Raymond Subes.

Similarly, before furnishing the wood-paneled living room, he addressed the architecture of the space. He gave the parquetry floor a dark stain. "This makes a more unified surface for a carpet," he says. "When you have a room the color of chestnut, you cannot have the floor the same color. Darkening it makes the room taller."

He installed low-wattage lighting in the ceiling ("You can never illuminate a room just with lamps, especially antique ones," he says. "You must have lights in the ceiling.")

Then he had gold, silver and platinum squares painted on the ceiling, to make it glow.

"The client said she didn't want a ‘boring' ceiling," Montoya recalls. "She asked me to do something so the apartment wouldn't look formal and traditional. We experimented with all kinds of things."

The palette is mostly gold, silver and ivory ("I wanted it glamorous," Montoya says). He reupholstered two Knole sofas from Paris with fabric the color of the beige Guillerme et Chambon 1950s club chairs. He placed a low table with a mirrored top in front of the red sofa and a chinoiserie low table from Jansen, circa 1940, between the Knole sofas. A tufted golden banquette in the corner serves as a foil to vintage French silvered-bronze table lamps, French gilt-bronze sconces and a spectacular round metal table with gilt acanthus leaves, designed by Gilbert Poillerat, a French artist whose designs for metal furniture and accessories were much sought after in Paris in the 1940s. Paintings by Hunt Slonem, Jo Cain and Wifredo Lam add to the sophistication of the room.

"He wanted to get us to that place where we loved everything," the wife says. "Juan and I liked shopping together. It was fun, and we took lots of long lunch breaks."

The library had been lipstick red. "I needed something more soothing," Montoya says. "To make it feel like a library, we put up dark red leather panels with macassar ebony moldings." A pair of Art Déco club chairs from the '40s and an Art Déco desk, both from France, float on the silk-and-wool carpet.

He infused the paneled dining room with a modern twist a huge 1950s Venini glass chandelier by the modernist architect Carlo Scarpa. Beneath it, he placed comfortable gondola chairs of his own design to complement an Art Déco macassar ebony table from France, which can be expanded to accommodate up to 12 guests.

Montoya's transformation of the master bedroom was complete. He designed the upholstered bed, the silk-and-wool carpet and the parchment-covered, wenge -framed custom closet doors to give the room an elegant, pulled-together look. "When you enter a bedroom, you should never see the bed on the side," he says. "You should see the entire bed in a picture-perfect arrangement."

Again, one must admire Montoya's mastery of the tricks of the trade. He dropped the soffits so he could install lights in the bedroom ceiling and create pockets for the two layers of curtains, sheer for day, blackout for night. Neither children nor pets can disturb its calm.

Juan Montoya should have his own reality show on television. In a year and a half, he took a plain Jane apartment and made it a drop-dead Hollywood glamour girl.