The Saltbox, Reinvigorated

View Slideshow

Even with a 2,620-page dictionary, you can feel at a loss for words to describe the work of Stephen Sills and James Huniford. Subtle seems totally inadequate. Transcendent comes closer, but not close enough. Somehow you never say quite enough. You call a room gray, but who has ever seen a gray like theirs? You point out the lanterns over the dining table, then hasten to add that they are oxidized just so and battered to perfection. Nobody will ever explain their particular magic, but everybody feels the result deep down inside, something these longstanding clients—both lawyers—learned years ago and hoped to achieve again at a weekend house in upstate New York.

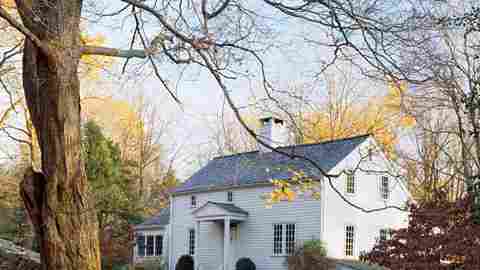

No place was ever more American than this, not the town, with its rubblestone walls and hills galloping like Paul Revere's horse, and not the house, a model of 18th-century purity. This aura of history is uncompromised even though 60 percent of the house is now new. From the street it still looks like a white Colonial box, the new construction almost invisible: extensions containing a spacious kitchen and master suite, and nearly 1,200 square feet of media room, music room, potting room and screen porch in the re-excavated basement. "You cannot draw a line and say this is where the old house ends and the new house begins," says Robert Rich, the New York-based architectural designer who devised this spatial solution. "I didn't want it to look as if someone had put on a big addition. There's some restoration, some renovation, some whole new cloth. It succeeds because there's a consistency of approach without being overtly historical."

Sills and Huniford are perhaps best known for colors that are unusual, quiet and fascinating. Here the living room is gray—or is it putty, or smoke, or fog, or mouse's back? Whatever you call it, it is one of the hardest colors to work with, for if it's the slightest bit wrong, it will absorb every ray of light. But Sills and Huniford get it so right: Their gray is deep and luminous, the result of patient work with a brush and a rag. If, as Huniford says, "the spirit of this house is very calming," it starts in this room with the color that has no name.

Huniford is six-foot-four, a little taller, in fact, to the top of his blond mop, and in the old rooms it's a remarkably short distance from his head to the ceiling.

"A high ceiling has always been the ultimate for us," Sills says. "What this house taught me is that a low ceiling can be extremely appealing." That is, if you approach it with their sensitivity. "It's all about the scaling of the pieces," he continues. "This is something that can never happen on a floor plan. It has to happen in the room itself."

Everybody equates fully upholstered pieces with comfort, but in this living room the designers felt they would be too deep, too massive. Instead, a wing chair was used as the prototype for a sofa that is shallower, more upright and considerably lighter in feeling. Tea-dyed to a soulful state, it couldn't be more hospitable. As companions to it, a pair of old wing chairs were taken down ten inches. Every piece was chosen with similar thoughtfulness. As American as the result feels, it is anything but. This chair is Dutch. That table is Swedish. A tray on the wall is Spanish. There are French things, too. The lack of literalness is what makes the room so interesting. "You don't get this feeling quickly," Huniford says. "The house was allowed to evolve."

"What people think of as perfection is often the spirit of imperfection," Sills says. Creating perfection is hard enough for most designers; discreetly slipping imperfections into their perfection is how these two challenge themselves. For example, the dining chairs are covered with a gold-on-periwinkle fabric that could be Fortuny, possibly the last fabric you would expect to see in a room this rustic. Sills explains: "When you visit old houses in this part of New York, they often have the most wonderful country furniture upholstered in weird old Venetian fabrics. In decoration some things don't make any sense, but they work." Sills and Huniford have a cache of tricks like these. New machined moldings were sanded to mellow their edges. Antique oak-plank flooring was installed in most of the original rooms as well as in the addition, with those nicely rusty old nail holes renailed.

In the extensions the rooms do breathe a little more. The ceiling climbs to nine feet in the kitchen, which has a modern island and limestone countertops and serious stainless-steel appliances. "Stephen didn't want it to look like a fitted kitchen, however," says Rich, adding, "I jumped on that one." Thus the upper cabinets do not stretch wall to wall; rather, they look like the odd old cabinet that has been hung. The ceiling climbs higher still, to just over 13 feet, in the master suite. Here the feeling is a little more European, with a lacy iron four-poster from Portugal and a set of romantic Italian mezzotints.

After all the sigh-inducing fabrics, the antiques you will never see the likes of again, the colors you could never duplicate, what is the one thing you cannot get out of your mind? In the living room there is an antique tripod table, painted a noncolor only time has the formula for. On it stands a big bushy begonia, an exotic variety with crinkly gray-green leaves edged in purple. Details like this cannot be bought in a showroom, but somehow Stephen Sills and James Huniford always know just where to find them.