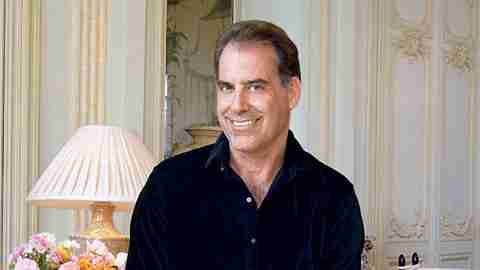

Tim Corrigan

View Slideshow

A well-designed house doesn't reveal all its secrets in the first five minutes," says Tim Corrigan. "Only over time does it show its depths to you." Corrigan is a founder and a principal in the firm Landmark Restoration, whose mission is, he says, "to appropriately update older houses to fit the needs of the clients while maintaining the integrity of the original architecture." When the designer returned to his hometown of Los Angeles after many years of residing in New York, Paris and Montecito, California, he naturally sought out a house "with the past in its bones."

Having restored and lived in a seventeenth-century Norman castle, a landmark Haussmann apartment in Paris, a Georgian town house in New York and a vast Mediterranean-style residence in Montecito that belonged to two generations of the J. P. Morgan family, Corrigan jumped at the chance to revive a 1913 Beaux Arts mansion in Hancock Park, buying it without so much as a walk-through. He had been in the house once, at a party, as a child.

"Everyone who grew up knowing this house thought it was a post office or a library," he recalls. "They didn't know it was a home." The imperial scale and august façade, which has French doors, classical columns and wide stone steps, conveyed an overbearing sense of grandeur. Dedicated to restoring—not remodeling—the property, Corrigan sought to "deinstitutionalize" it.

“In both its architectural and social pedigree, Los Tiempos, as it had come to be called, is something of a Los Angeles landmark”.

In both its architectural and social pedigree, Los Tiempos, as it had come to be called, is something of a Los Angeles landmark. Commissioned by Dr. Peter Janss, who was part of the real estate dynasty that developed Westwood Village and Holmby Hills, Los Tiempos was designed by architects J. Martyn Haenke and W. J. Dodd, who worked with Julia Morgan on William Randolph Hearst's 1914 Examiner building.

In the mid-fifties the property passed into the hands of Norman Chandler, the publisher of the Los Angeles Times , and his wife, Dorothy, who raised funds to build the Los Angeles Music Center. The couple, who frequently held large receptions at Los Tiempos, poured a concrete terrace over much of the backyard. "It took three months of jackhammering to get the cement out," Corrigan says. "It was a solid three feet deep."He brought in more than three hundred trees and rosebushes for the relandscaping.

The Chandlers had also paneled an ornate Victorian-style dining room with simple French boiseries, installed eighteenth-century faux-mar-bre columns from a Venetian palazzo in the living room and extended the rear of the house to accommodate an eighteenth-century salon that a German prince and music patron had created for Mozart in a castle outside Munich. Corrigan preserved the interior modifications but sought "to revitalize the house and make it younger,"he says. "One of my key goals was lightening and brightening.

"Beaux Arts homes can have a very formal, stuffy look," Corrigan adds. "But they also tend to have wonderful classical lines, great volumetric spaces and a cleanness. The challenge is to make them really comfortable." In order to soften the living room, with its cold gray travertine walls—constructed from the same material used to build the Music Center—and imposing terrazzo floors, Corrigan used sea grass carpeting and sandblasted, scored and stained the marble to resemble a warm French limestone. Creamy cotton brocade sofas reinforce a bright, casual look.

The library, on the other hand, has been fashioned quite purposefully to evoke a nineteenth-century gentleman's study. Napoleon III and Louis XIII pieces complement portraits by Henri Fantin-Latour, Emile Lévy and Jacques-Louis David. An assembly of obelisks, the earliest dating back to 1792, sits just beyond a set of doors. "I'm intrigued by the way art and history have influenced one another, whether in literature or in furniture. I think houses are so much more interesting when the art and design and landscape are integrated."

In the course of his research, Corrigan came across a book on sixteenth-century garden design, which inspired him to place a long reflecting pool outside, on the axis of the dining table. Using forced perspective—the far end is two feet narrower, and boxwood spheres are spaced closer together from front to back—it is a marvel of optical illusion, looking much longer than its thirty feet.

"In both its architectural and social pedigree, Los Tiempos, as it had come to be called, is something of a Los Angeles landmark".

Inside, Corrigan maintained the bleached woodwork, the peach velvet walls and maroon velvet balustrade leading up to the master suite, which still has the original gilt-bronze door-bell. The space is furnished with Biedermeier pieces and opens onto terraces on three sides. For the guest bedrooms, raspberry upholstery fabrics, a lipstick-colored bookcase and a flowered screen once owned by Pamela Harriman populate an intensely feminine chamber, while a Wedgwood-blue-and-black palette is used for the room slept in by presidents Kennedy and Nixon during the years Los Tiempos served as an unofficial western White House.

"I wanted there to be a playfulness, especially when it came to the furniture and art," says Corrigan, "and I didn't want to be a purist in any one style." His pleasure in combining elements from different periods is reflected in the furniture throughout, from the Chandlers' Steinway piano signed by Van Cliburn and Rachmaninoff and the eighteenth-century inlaid-mahogany throne chair belonging to a governor of the Dutch West Indies to the twelve-foot-long celadon sofa from the Doris Duke estate.

"Designing my own house, I can take greater risks," Tim Corrigan admits, "such as bringing together an African sculpture and an eighteenth-century English commode. I have to work to convince clients that disparate pieces make an interior dynamic. I'll always try to achieve the same result, but with my own house, it's easier to get there."